Peace and Safety for Your Twentieth of March: If [happiness] be absent, ALL our actions are directed towards attaining it.

Peace and Safety to the Epicureans of today, no matter where you might be – Happy Twentieth!

Today is the Twentieth of March, the day of the month designated by Epicurus to remember Metrodorus and himself and the philosophy of happiness they developed and taught. Today is also “International Happiness Day.” #InternationalDayOfHappiness

Epicurus held that happiness is the goal set for us by Nature, and so happiness was at the center of his philosophic system. The word “happiness,” however, has many different meanings, and Epicurus went to great lengths to explain his own definition. In Epicurean philosophy, true happiness is based on pleasurable living rather than on abstractions such as “virtue” or imaginary places such as “heaven” and “hell.” In Epicurean terms, the real test of things that bring “happiness” is therefore whether a thing is in fact productive of pleasurable living.

It’s therefore very interesting to review the “Ten Keys Guidebook” provided at the International Happiness Day page. The Guidebook contains no no reference to Epicurus, as best I can find, either in the quotes or in the references at the end. There are, however, many references to modern authorities for statements such as “Happiness is a deep sense of flourishing, not a mere pleasurable feeling or fleeting emotion, but an optimal state of being” which is attributed to Matthieu Ricard. Mark that sentence down for at least two warning flags: (1) the implicit tribute to Aristotelian “flourishing, and (2) the derogatory “mere” in reference to pleasurable feelings.

Reading further, it appears that the recommendations in the Guidebook come down to these ten:

(1) Do things for others.

(2) Connect with people.

(3) Take care of your body.

(4) Life life mindfully.

(5) Keep learning new things.

(6) Have goals to look forward to.

(7) Find ways to bounce back.

(8) Look for what’s good.

(9) Be comfortable with who you are.

(10) Be part of something bigger.

Of these, I would say that an ancient Epicurean could without hesitation embrace one of these – number three. Each of the others embraces topics on which Epicurus gave explicit or implicit warnings, and remembering those here is a good exercise:

(1) Do things for others. – Epicurus identified friendship as central to happiness, and stated that on occasion we will either die for a friend. However not all “others” are “friends.” Thus Epicurus clearly warned us about being overly generous in viewing “others” as “friends,” and in PD39 he tells us: “39. The man who best knows how to meet external threats makes into one family all the creatures he can; and those he can not, he at any rate does not treat as aliens; and where he finds even this impossible, he avoids all dealings, and, so far as is advantageous, excludes them from his life.”

(2) Connect with people. – “People?” This merits the same warning as item (1).

(3) Take care of your body. – Yes! Commentators frequently mention that Epicurus taught a variation of “sound mind in a sound body” so this is the 1/10 of this list that I think every Epicurean could enthusiastically embrace. The only limitation that immediately comes to mind is that mentioned above in respect to item (1) that on occasion we will die for a friend.

(4) Life life mindfully. – What does “mindfully” mean? Epicurus left many teachings on how to think, but a specific one that comes to mind is “PD 16. Chance seldom interferes with the wise man; his greatest and highest interests have been, are, and will be, directed by reason throughout his whole life.”

(5) Keep learning new things. – What new things? Epicurus warned that knowledge is not to be pursued for the sake of knowledge itself, but for the happiness that knowledge can bring. There is an important difference in suggesting that we always “keep learning new things” in that “new things” need to be focused on those things that will make us happy, not on things that are useless toward that goal, or even counterproductive. As Torqatus stated in “On Ends,” – “You are pleased to think [Epicurus] uneducated. The reason is that he refused to consider any education worth the name that did not help to school us in happiness. Was he to spend his time, as you encourage Triarius and me to do, in perusing poets, who give us nothing solid and useful, but merely childish amusement? Was he to occupy himself like Plato with music and geometry, arithmetic and astronomy, which starting from false premises cannot be true, and which moreover if they were true would contribute nothing to make our lives pleasanter and therefore better? Was he, I say, to study arts like these, and neglect the master art, so difficult and correspondingly so fruitful, the art of living? No! Epicurus was not uneducated: the real philistines are those who ask us to go on studying till old age the subjects that we ought to be ashamed not to have learnt in boyhood.

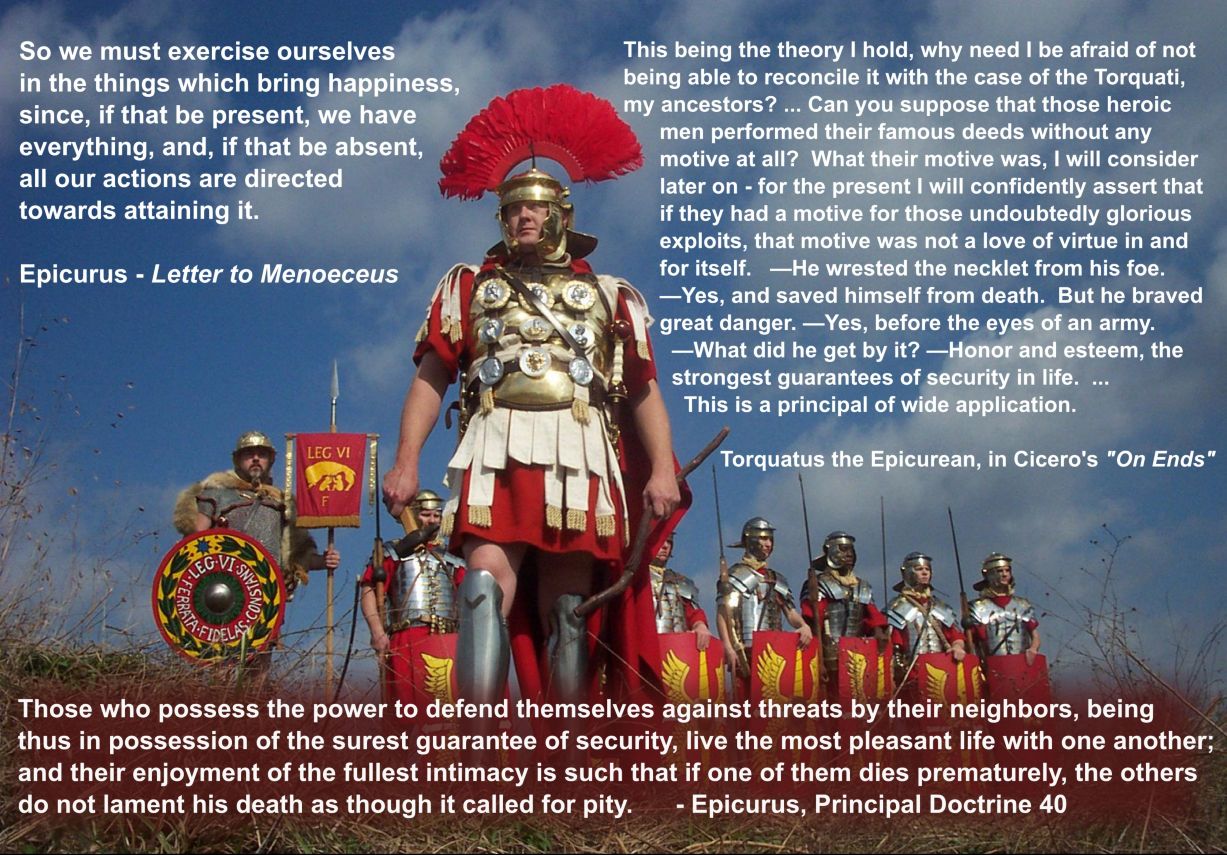

(6) Have goals to look forward to. What goals? Many of the surviving Epicurean texts are devoted to showing the error in goals such as political or military conquest, fame, fortune, and goals that are intoxicating rather than fulfilling. We are constantly bombarded by suggestions today that we live purpose-driven lives, but the ultimate issue is “to what purpose?” Epicurus had very specific advice about our purpose: “So we must exercise ourselves in the things which bring happiness, since, if that be present, we have everything, and, if that be absent, all our actions are directed towards attaining it.”

(7) Find ways to bounce back. This one is probably innocuous enough because it is so ambiguous. There are many ways to look at this issue in Epicurean philosophy, but one of the most immediate is to remember that life is short and we must make what we can of it while we have the time. VS47. “I have anticipated you, Fortune, and entrenched myself against all your secret attacks. And we will not give ourselves up as captives to you or to any other circumstance; but when it is time for us to go, spitting contempt on life and on those who here vainly cling to it, we will leave life crying aloud in a glorious triumph-song that we have lived well.”

(8) Look for what’s good. What is “good”? It is very dangerous to speak loosely, as if everyone understands what “the good” means. Epicurus devoted much work to pointing out how “virtue” is not the same as “the good,” and one of the best formulations of this comes down to us from Diogenes of Oinoanda: “If, gentlemen, the point at issue between these people and us involved inquiry into «what is the means of happiness?» and they wanted to say «the virtues» (which would actually be true), it would be unnecessary to take any other step than to agree with them about this, without more ado. But since, as I say, the issue is not «what is the means of happiness?» but «what is happiness and what is the ultimate goal of our nature?», I say both now and always, shouting out loudly to all Greeks and non-Greeks, that pleasure is the end of the best mode of life, while the virtues, which are inopportunely messed about by these people (being transferred from the place of the means to that of the end), are in no way an end, but the means to the end. Let us therefore now state that this is true, making it our starting-point.”

(9) Be comfortable with who you are. And if you are mired in pain? If this means that you should accept everything about yourself and not make an effort to change the things that can be changed, then this is the worst sort of advice. No doubt the writer would dispute this as the meaning, but we can never forget that happiness takes effort to achieve, and if we find ourselves in circumstances where we cannot be happy, we must make an effort to change those circumstances. As Thomas Jefferson said to his friend William Short, “I take the liberty of observing that you are not a true disciple of our master Epicurus, in indulging the indolence to which you say you are yielding. One of his canons, you know, was that “that indulgence which prevents a greater pleasure, or produces a greater pain, is to be avoided.” Your love of repose will lead, in its progress, to a suspension of healthy exercise, a relaxation of mind, an indifference to everything around you, and finally to a debility of body, and hebetude of mind, the farthest of all things from the happiness which the well-regulated indulgences of Epicurus ensure; fortitude, you know is one of his four cardinal virtues. That teaches us to meet and surmount difficulties; not to fly from them, like cowards; and to fly, too, in vain, for they will meet and arrest us at every turn of our road. Weigh this matter well; brace yourself up….”

(10) Be part of something bigger. “Bigger?” This seems like an appeal to religion or to idealism of another kind – the type of ambiguous goal that the Epicureans frequently attacked in the misuse of “virtue.” The “bigger picture” is exactly what Epicurus focused on teaching, and it has nothing to do with mystical “bigger” goals. The study of Nature reveals to us that there are no “bigger” ideals driving the universe toward or through “divine fire.” As Lucretius described in the opening of Book One of his poem, the pursuit of pleasure is what drives all living things, including men. It is very dangerous to think that there is “something bigger” than Nature’s own guide for living beings.

In sum, the Guidebook has much of interest in it, and much that is very helpful to consider. But in the end platitudes are of no use – and are in fact dangerous – because the only test of successful living techniques is whether we in fact are able to live happily through those techniques. As Epicurus said, PD10. “If the things that produce the pleasures of profligate men really freed them from fears of the mind concerning celestial and atmospheric phenomena, the fear of death, and the fear of pain; if, further, they taught them to limit their desires, we should never have any fault to find with such persons, for they would then be filled with pleasures from every source and would never have pain of body or mind, which is what is bad.”

To illustrate the contrast between what the world thinks leads to happiness, and what Epicurus taught, see the attached graphic. This is to remind us that the pursuit of happiness regularly involves engaging in activities which seem furthest removed from happiness, but which are required at times by circumstanes. No amount of “happy thinking” is sufficient to deal with every challenge the world throws at us. The “Happiness Guidebook” cites Victor Frankl as writing: “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms: to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.” While this might be taken to mean other things, the most clear implication of these words is that pain can be overcome by force of will. That attitude is Stoicism, not Epicurean philosophy. Epicurus taught that the wise man will feel emotion more strongly, not less strongly, than the unwise. Reality brings us both pleasure and pain, and it is our role to act accordingly to maximize the pleasure and minimize the pain – willpower does not stop a javelin or a bullet. That’s why it isn’t stoicism, but taking action to study nature and live wisely according to the doctrines of Epicurus, that is the true path to happiness.

________

As Seneca recorded: Sic fac omnia tamquam spectet Epicurus! So do all things as though watching were Epicurus!

And as Philodemus wrote: “I will be faithful to Epicurus, according to whom it has been my choice to live.”

Additional discussion of this post and other Epicurean ideas can be found at EpicureanFriends.com