Library

The ancient Epicurean texts that remain to us today are available freely on the internet in many different translations. This page provides links to various translations of the core works and notes as to the available commentaries and more modern works.

There are many websites and articles available on the internet, with many varying opinions as to the true teachings of Epicurus. This website strongly recommends that the best place to start the study of Epicurus is Norman DeWitt’s Epicurus And His Philosophy. Other sources and commentaries are referenced in the list below, but until you have read DeWitt you have not read a sympathetic summary of the philosophy as an ancient Roman or Greek would have known it. Only when you have heard the pro-Epicurean side are you fairly equipped to deal with the legions of critics of Epicurus, and only then can you do justice in rendering a fair verdict on Epicurus’ conclusions.

Professor Dewitt devoted much of his professional life to articles and books on Epicurus, and understanding his perspective is the best way to prepare yourself for the details of what you will read in the Epicurean texts. A summary essay written by Professor DeWitt which gives a taste of his assessment of Epicurus can be found in “Philosophy For The Millions.”

After a grounding from a sympathetic writer like DeWitt, who will acquaint you with the general structure of Epicurus’ life and ideas, much more detail can be found in the following sources:

READING LIST AND QUICK LINKS:

Diogenes Laertius Book X – This is the primary source for the great majority of information we have about Epicurean philosophy. It contains both a biography of the life of Epicurus and core original material about his philosophy. Virtually all the commentary you may read about Epicurus is based on material taken from this source, so after you have a general grounding on the overall picture from a competent source such as DeWitt, Diogenes Laertius is a key place to come to test your observations. The translation by CD Yonge is here. The R D Hicks translation with side-by-side Greek and English is here. The Wikisource version is here. The excellent Perseus edition is here in Greek and here in English. Norman DeWitt’s translation of the letter to Menoeceus is here. Cyril Bailey was not a fan of many aspects of Epicurean philosophy, and his commentaries must be read with that in mind. Nevertheless, his translations (while also subject to criticism as highlighted by DeWitt) are probably the most accessible free source for comparing the translations to the Greek sources. Bailey’s most accessible translation of Diogenes Laertius is in Epicurus – The Extant Remains, which contains side by side Greek and English with extensive notes. Here are quick links to the major sections: Principal Doctrines, Vatican Sayings, Letter to Herodotus, Letter to Pythocles, Letter to Menoeceus, Other Fragments, Letter to Idomeneus, The Will of Epicurus, Diogenes Laertius’ Life of Epicurus

Epicurean Fragments – In addition to the above link to Bailey’s Extant Remains, a site that has recently become one of the best sources for Epicurean Fragments is Attalus.org. This contains a good source for Cassius Longinus’ correspondence with Cicero which mentions Epicurean philosophy.

Lucretius: On the Nature of Things – Following closely behind Diogenes Laertius in significance is the lengthy poem in which Lucretius faithfully captures Epicurean doctrine, probably as originally written in narrative form in Epicurus’ “On Nature.” This poem was written for an audience well versed in the details of life and culture in the Roman world of the first century BC, so it can be confusing unless you first understand the general outlines of the philosophy and the topics you can expect to encounter. That makes the poem a poor place to start one’s reading into Epicurus, but an excellent place to go once you understand the basics. The version used in the Lucretius Today Podcast, along with Munro and Bailey is here. My new favorite public domain version in terms of understandable text, good footnotes, and side-by-side Latin and English is the Daniel Browne (publisher) version from 1743. Unfortunately this text uses the old “f” for “s” font style – further discussion about this version is here. For a new reader, this text is among the most understandable, and precise textual issues can be checked against the later Bailey and Munro versions. The Bailey version is here. The Munro version is here. Also see also this website for a digital transcription of the Munro and Bailey versions. If you are looking for the latest and most authoritative copyrighted edition, I suggest the version by Martin Ferguson Smith. The 1743, Munro, Bailey, and Smith versions are prose and make no effort to render the text in poetic form. If you wish a version that attempts to capture the poetry at the expense of literal accuracy, one of the best is Humphries’ “The Way Things Are. The 1924 Loeb Edition by Rouse, with Latin and English on facing pages, is here.

Lucretius: On the Nature of Things – Following closely behind Diogenes Laertius in significance is the lengthy poem in which Lucretius faithfully captures Epicurean doctrine, probably as originally written in narrative form in Epicurus’ “On Nature.” This poem was written for an audience well versed in the details of life and culture in the Roman world of the first century BC, so it can be confusing unless you first understand the general outlines of the philosophy and the topics you can expect to encounter. That makes the poem a poor place to start one’s reading into Epicurus, but an excellent place to go once you understand the basics. The version used in the Lucretius Today Podcast, along with Munro and Bailey is here. My new favorite public domain version in terms of understandable text, good footnotes, and side-by-side Latin and English is the Daniel Browne (publisher) version from 1743. Unfortunately this text uses the old “f” for “s” font style – further discussion about this version is here. For a new reader, this text is among the most understandable, and precise textual issues can be checked against the later Bailey and Munro versions. The Bailey version is here. The Munro version is here. Also see also this website for a digital transcription of the Munro and Bailey versions. If you are looking for the latest and most authoritative copyrighted edition, I suggest the version by Martin Ferguson Smith. The 1743, Munro, Bailey, and Smith versions are prose and make no effort to render the text in poetic form. If you wish a version that attempts to capture the poetry at the expense of literal accuracy, one of the best is Humphries’ “The Way Things Are. The 1924 Loeb Edition by Rouse, with Latin and English on facing pages, is here.

Cicero’s “On Ends” – One of the most clear and extended presentations of Epicurean ethics anywhere, even exceeding Diogenes Laertius in clarity, is Torquatus’ presentation of Epicurean philosophy in this work. Cicero was an enemy of Epicurus and his commentary cannot be trusted, and this presentation by Torquatus must also be considered carefully. However in general this is considered to be a faithful reproduction of core Epicurean ethics. 1931 Loeb / Rackham (Alternate Rackham translation)

Cicero’s “On The Nature of the Gods” – Key aspects of Epicurean views on the true nature of the gods are lost to us, but this short presentation given in the name of Velleius’ is one of the important remaining sources. Look for the section at this link which begins: “After this, Velleius, with the confidence peculiar to his sect, dreading nothing so much as to seem to doubt of anything, began as if he had just descended from the Council of the Gods and Epicurus’ intervals of worlds….” (Yonge translation)

Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations” – This work contains important commentary from Cicero and quotations from Epicurus on several key points, including the nature of pleasure and the good, such as: “I have often inquired of those who have been called wise men what would be the remaining good if they should exclude from consideration all these pleasures [pleasures which are perceived by taste, or from what depends on hearing music, or abstracted from ideas raised by external objects visible to the eye, or by agreeable motions, or from those other pleasures which are perceived by the whole man by means of any of his senses], unless they meant to give us nothing but words. I could never learn anything from them; and unless they choose that all virtue and wisdom should vanish and come to nothing, they must say with me that the only road to happiness lies through those pleasures which I mentioned above.” (Yonge translation). Perhaps a better source for all of Cicero’s key works in one place is this edition by Yonge.

Diogenes of Oinoanda – The inscription commissioned by the Epicurean Diogenes is fragmentary, but contains excellent information which fleshes out important aspects of Epicurean views. The best translation is by Martin Ferguson Smith which is available at this website in Spain, but a less complete version by C. W. Chilton is also available in book form.

Lucian – This Greek writer is not considered to be an orthodox Epicurean, but his works display much Epicurean influence and it can be inferred that many of his arguments and positions derive from that source. An essay of particular interest is Lucian’s HERMOTIMUS. A good source for Lucian’s collected works is here.

Frances Wright: A Few Days In Athens – This remarkable work written by a friend of Thomas Jefferson in the early 1800’s must be considered to be a secondary source, as its contents are reconstructed without access to the majority of core texts and teachers that existed in the ancient world. However it does an excellent job in presenting in fictional form many important aspects of Epicurean philosophy, particularly as it relates to Stoic and other competing Greek philosophic ideas. See also the website www.AFewDaysInAthens.com dedicated to the book, with audio version.

Gassendi: Life And Doctrine of Epicurus: A transcription and a link to the PDF original of Volume III of Thomas Stanley’s 1660 “History of Philosophy” is here.

Philodemus: On Methods of Inference – Philodemus’ works are fragmentary and as such are useful mainly for further study after the reader has a good grasp of Epicurean philosophy. This version, translated by Phillip and Estelle De Lacy, contains excellent discussion of Epicurean epistemology, including differences between Epicurus and Aristotle.)

Philodemus: On Rhetoric – This work contains fragments relevant to education and other issues. (Alternate Source) Hubbell translation.

Website Links – As of this writing the best source for links to internet web pages focused on Epicurean philosophy is found at www.EpicurusCentral.wordpress.com.

Modern Epicurean Works – For readers who already have a general grasp of Epicurus, two modern books of special note are Hiram Crespo’s “Tending the Epicurean Garden” and Haris Dimitriadis’ “Epicurus And The Pleasant Life.”

Other Modern Commentaries – Most modern commentaries are an inferior starting point for new students of Epicurus. Unlike DeWitt’s Epicurus and His Philosophy, they make little effort to present Epicurus in a sympathetic light, and the new reader is left to wonder how the philosophy ever appeared persuasive to anyone in the ancient world. Modern academic works are mostly critical, especially of Epicurean ethics, and in many respects DeWitt’s book is the only way to get the Epicurean viewpoint which should be understood first before the arguments of the critics can be evaluated. Of special note, however, is Gosling & Taylor’s “The Greeks On Pleasure.” While not specifically focused on the Epicureans, this work explains the primary views of pleasure before Epicurus, and shows how he revolted against Plato and other Greek anti-pleasure philosophers. Only by reviewing this context in which Epicurus wrote can otherwise difficult passages like his view of “absence of pain” be fit into a coherent and persuasive framework of ordinary pleasure. Without this context Epicurus can be (and frequently is) made to sound like a Stoic in disguise, but with the context in view it is clear that Epicurus’ views were consistent and well-deserving of hostility from the Stoics, who violently disagreed with him. This book can be difficult to find outside a library, but it is very valuable for anyone researching aspects of Epicurus which are difficult to understand, standing alone, but which become clear as responses to earlier arguments.

Note: The likeness in the etching at the top of this page is that of Hugh Munro, translator of Lucretius.

For additional links of interest, see the following:

PRIMARY SOURCES: The Original Texts

- Diogenes Laertius: Lives And Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Chapter XII– This work is the most important remaining source of information about Epicurean philosophy, and it contains a number of letters represented to have been written by Epicurus himself.

- C.D. Yonge – 1853 Edition of Bohn’s Classical Library. – Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org –

- Lucretius: On The Nature of Things (De Rerum Natura) -Second only to Diogenes Laertius in importance, this Latin poem written in about 50 BC is sweeping in scope. Written as an introduction to Epicurean philosophy by an enthusiastic and knowledgeable convert, on those areas which Lucretius’ addresses this poem provides invaluable insight into Epicurean philosophy. Much of the poem is devoted to showing how phenomena such as lightning are caused by Nature, and not by gods, and thus to showing why men should throw off the oppression of religion. With the advance of science over the centuries these matters are not of as much immediate concern as they were in Lucretius’ time, but his poem nevertheless provides an abundance of ethical and historical insight about Epicurean philosophy, especially in the opening sections of each of the six books.

- H.A.J. Munro

- 1908 Edition, Bohn’s Classical Library– Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org – This edition contains an interesting biography of Munro, who is perhaps the leading modern translator of On The Nature of Things.

- Three Volumes, Notes, Text, and Translation, Fourth Edition, Finally Revised, Printed 1893 Deighton Bell & Co., London. This is the definitive scholarly translation by the leading 19th century scholar of Lucretius.

- Volume 1 – Text: Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org

- Volume 2 – Explanatory Notes: Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org

- Volume 3 – Translation: Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org

- John Mason Good

- 1805 Edition – This is a very flowery poetic translation which readers may find more useful for the extensive introduction, and notes, than for the actual text of the poem itself.

- Volume I – Google Books

- Volume II – Google Books

- 1805 Edition – This is a very flowery poetic translation which readers may find more useful for the extensive introduction, and notes, than for the actual text of the poem itself.

- Ian Johnston, Vancouver Island University, 2010

- Cyril Bailey

- Oxford Press, 1910: Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org This edition is more recent than Munro and of similar scholarly value. Munro’s edition, and this one, are far superior in readability to the modern reader than most other editions. Bailey published a volume with many annotations, but that does not appear to be available currently.

- H.A.J. Munro

- Cicero: On the Ends of Good And Evil (De Finibus Malorum et Bonorum)– Although he was not an Epicurean himself, and in some ways distorts the views of Epicurus to place them in an unflattering light, Cicero devoted long segments of his works to presentations of Epicurean positions.

- H. Rackham – 1914 Edition of the Loeb Classical Library Volume of Cicero. – Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org –

- Cicero: Tusculun Disputations, On The Nature of the Gods, and The Republic –

- C.D. Yonge – Searchable text

- C. D. Yonge – 1894 – Archive.org

- Andrew Peabody 1886 Translation of Tusculun Disputations

- Seneca’s Letters – Seneca, like Cicero, was not an Epicurean, but Seneca preserved a great many of Epicurus’ sayings and the views of the Epicureans on many subjects

- Volume I

- Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org

- Volume II

- Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org

- Volume I

SECONDARY SOURCES: Treatises and Commentaries

- Norman W. DeWitt

- Epicurus and His Philosophy – This treatise is essential reading for anyone interested in Epicurus.

- Scribd – Google Books – Archive.org – Search on Abebooks

- Epicurus and His Philosophy – This treatise is essential reading for anyone interested in Epicurus.

- Cyril Bailey

- Norman W. DeWitt

- St. Paul and Epicurus – This book is available in full at Epicurus.info

- St. Paul and Epicurus – This book is available in full at Epicurus.info

OTHER SOURCES: Articles and Essays

- Norman W. DeWitt

- Philosophy for the Millions – PDF- The Classical Journal, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Jan., 1947), pp. 195-201

- St. Paul and Epicurus – Full book on Epicurus.info / Epub Format

- The Canon, Reason, and Nature – Chapter VII of Epicurus and His Philosophy

- Sensations, Anticipations, and Feelings – Chapter VIII of Epicurus and His Philosophy

- Organization and Procedure in Epicurean Groups – PDF

- A. A. Long

- Stephen Rosenbaum

Notes:

In my view, it is best to compare several translations for any important passage. A key example of this is in Diogenes Laetius’ “Life of Epicurus.” In most cases, I prefer Bailey’s translation for its more up-to-date scholarship, additional notes, and easier-to-read phrasings. In at least one key passage regarding the crucial Canon of Truth, however, Bailey’s choice of words can obscure a major issue. Here is a key passage, marked as paragraph 31 in Bailey and XX in Yonge:

- Bailey: “Logic they reject as misleading. For they say that it is sufficient for physicists to be guided by what things say if themselves. Thus in the Canon Epicurus says that the tests of truth are the sensations and concepts and feelings; the Epicureans add to these the intuitive apprehensions of the mind.” … The concept they speak of as an apprehension or right idea or thought or general idea stored in the mind, that is to say a recollection of what has often been presented from without….

- Yonge: Dialectics they wholly reject as superfluous. For they say that the correspondence of words with things is sufficient for the natural philosopher, so as to enable him to advance with certainty in the study of nature. Now, in the Canon, Epicurus says that the criteria of truth are the senses, and the preconceptions, and the passions. But the Epicureans, in general, add also the perceptive impressions of the intellect. … By preconception, the Epicureans mean a sort of comprehension as it were, or right opinion, or notion, or general idea which exists in us; or, in other words, the recollection of an external object often perceived anteriorly.

In my reading, most translators use the word preconception or anticipation to indicate that what Epicurus was referring to here was not simply a “logical construction” such as most of us probably think of when we use the word “concept.” I won’t belabor this issue here (because I have elsewhere!) but would simply refer the reader to Chapters 6 and 7 of DeWitt’s Epicurus and His Philosophy for an extensive discussion of the nature of anticipations. If the student of Epicurus is to keep in view the extent to which Epicurean philosophy is a rejection of Platonism and Aristotelianism, it is essential that the implications of Epicurus rejecting “reason” as a component of the Canon of Truth be clearly understood.

Especially for those familiar with basic Epicurean concepts, the audiobook version of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura by Charlton Griffin available at Audible.com is excellent. Charlton Griffin’s verbal performance of Rolfe Humphries’ English translation is an excellent presentation of that material.

Further Notes –

On John Rist’s “Philosophy of Epicurus”:

8/27/16 – I was asked about this book recently and recall that I object to the preface, where Rist deprecates the work of DeWitt. I also note that in his chapter on canonics Rist continuously uses the term “general concepts” rather than “preconceptions” or “anticipations” in a way that prejudges the issue of what anticipations are.

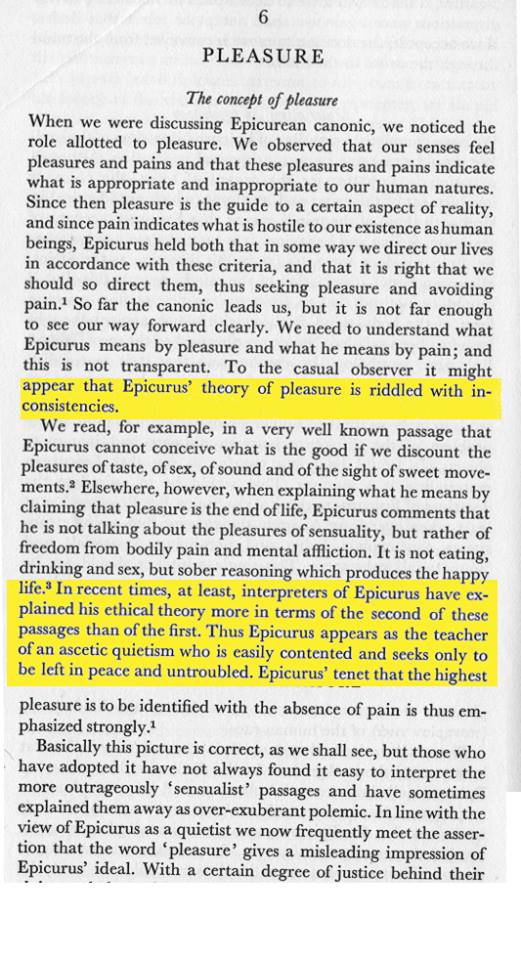

2/22/16 – Yesterday I posed the question whether, if we look to the example of babies and young animals as Epicurus did, we would decide that it would be better to view “rest” as something we do so that we can “pursue pleasure,” or better to view the pursuit of pleasure as something we do in order to rest. The reason I asked that question is that there is a strong view among modern commentators to allege that Epicurus was an “asecetic quietist” who “only wanted to be left in peace and untroubled” – meaning that Epicurus was someone who chose rest and retirement over joy and action.

I know everyone does not share my concern about this, so to illustrate why I think this deserves attention, here is the introductory paragraph on “Pleasure” in “Introduction to Epicurus” written by John Rist and published by Cambridge University Press. This is the kind of book that impressionable young students looking to learn about Epicurus find in modern libraries.

Most people who pick this up won’t realize the implication when Rist tells them in the Preface that “As for Dewitt’s Epicurus and His Philosophy, it is essentially a work of special pleading, and his theses about Epicurus’ canonic and the general nature of the ethical writings have not won wide acceptance.” Instead, they will think that DeWitt was a nut, and that it is unchallenged truth that Epicurus was an “ascetic quietist.” Here is that very conclusion stated in black and white and highlighted in yellow:

Please note: All material on this website is from sources that are believed to be either in the public domain or usable here within proper fair use standards. In most cases and with few exceptions, text on this site has been taken from the volumes sited below. Due to the age of these volumes and the awkwardness that results from attempts at literal translations, the versions found here may contain slight paraphrasing and punctuation changes. Such editing is for purposes of clarity only, and great efforts are taken to remain true to the original meaning. Readers are always urged to consult the original volumes, in the original Latin and Greek if possible. Please email any suggestions or corrections to the this website so that updates can be made in future editions.Loeb Editions of the public domain editions for many classic Greek and Roman authors can be accessed here (Loebolus) and here Ed Donnelly.com.