Three General Points About the Canon of Truth

Please go here to view the full article with the latest revisions. The version as of 5/20/18 is below.

In yesterday’s discussion of Chapter 8 (Sensations, Anticipations, and Feelings) of Norman DeWitt’s book, the comment was made that there is likely a lot of confusion about what is meant by the “Canon of Truth.” The word “canon” is rarely used today, and when it is used it generally has the meaning listed first at Dictionary.com: “an ecclesiastical rule or law enacted by a council or other competent authority and, in the Roman Catholic Church, approved by the pope.” In fact there are fifteen separate definitions listed at Dictionary.com all but one of which would be misleading if we applied it to Epicurus’ canon (see below).

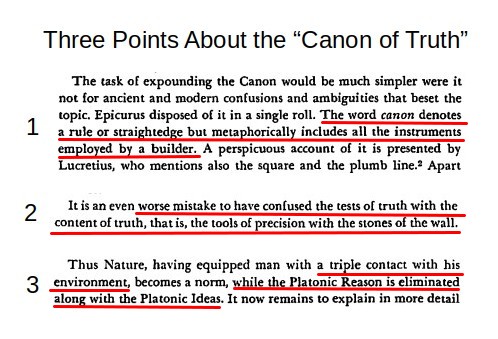

Before getting to those modern usages, it is helpful to look at DeWitt’s observations about the Canon. DeWitt devotes a full chapter to the subject, but it seems to me that three of his points are probably the most important: They are (starting at page 121 of Epicurus and His Philosophy) –

As I understand DeWitt, the points he is making are:

- The Epicurean Canon of truth is NOT a set of conclusions or opinions about any subject or object whatsoever. The Epicurean Canon of truth is a set of three tools of precision, or measuring devices, analogous to yardsticks, straight edges, plumb lines, or any other type of measuring instrument by which we receive data which is only thereafter evaluated by the mind. Modern technology has added many other tools which could be used as other analogies, for examples those which are included at this Wikipedia article, which opens with the following, much or all of which probably applies to each of the three canonical faculties: “A measuring instrument is a device for measuring a physical quantity. In the physical sciences, quality assurance, and engineering, measurement is the activity of obtaining and comparing physical quantities of real-world objects and events. Established standard objects and events are used as units, and the process of measurement gives a number relating the item under study and the referenced unit of measurement. Measuring instruments, and formal test methods which define the instrument’s use, are the means by which these relations of numbers are obtained. All measuring instruments are subject to varying degrees of instrument error and measurement uncertainty.” The takeaway is: Do not look to the Canon of Truth to give you a conclusion or an opinion. The task of forming conclusions and opinions is in the mind; the task of providing data for those conclusions comes through the canonical faculties. Smell the apple, feel its firmness, taste its flavor, look at its color, feel whether it is pleasing to eat – but do not expect these measurements alone to tell you whether to eat any particular apple.

- It is a major mistake to confuse the tools of precision, or the measuring devices, with the objects which they are designed to measure. In DeWitt’s words, the “tests of truth” are not to be confused with the “content of truth.” For modern examples, a speedometer measures speed, but is not itself speed. An pedometer measures paces, but is not itself paces. A ruler measures length, but is not itself the thing that has the length we are measuring. A straight edge is an indication of straightness, but is not itself the straight (or crooked) item that is being judged. So in Epicurean terms, the Canon of truth is a set of measuring devices by which we receive data about those things with which we come into contact, but the Canon is not itself those things which we are measuring. Our sight of a bird is data about its color, shape, size, texture, and the like, but our sight of a bird is not itself a bird. Our feeling of pleasure at seeing a bird is a measure of our mental and physical positive reaction at, for example, seeing a bluebird, but which might be a negative reaction if what we see is not a bluebird, but a vulture. Our reaction to the bird, however, is an instance of experience that is being measured, it is not equivalent to some quantity of pain or pleasure inherent within the bird. The subject of our “anticipation” in regard to observation of a bird is controversial, and our interpretation will depend on our personal reading of the Epicurean texts and our position on what an “anticipation” really is. Regardless, however, whether an anticipation is a “concept,” as some argue, or an intuitive faculty of some kind (as DeWitt argues) the anticipation is NOT the same as the bird itself. The takeaway is: do not think that the measuring device is the same as the thing being measured. Measure the apple to estimate its size, but do not expect to eat the measurement.

- The Epicurean Canon of truth is a triple contact with your environment. In DeWitt’s words, nature has equipped man with the canonical faculties as a triple contact with his environment. The “triple contact” part if clear enough, but the “with his environment” is frequently overlooked. The Canon of Truth is not a mystical compilation of information about about the universe at large. The Canon of Truth was not enough to enable an ancient Athenian to determine what the other side of the moon looked like – many things are beyond the reach of our present observational faculties. For those things beyond the reach of direct observation, we must resort to comparison, analogy, and other methods of reasoning based on inference (such as is discussed in the surviving portions of Philodemus’ On Methods of Inference). Our conclusions about those matters are necessarily speculative, and we must consider the principles of inferential thinking preserved in PD’s 22 – 25:

- PD 22. We must consider both the ultimate end and all clear sensory evidence, to which we refer our opinions; for otherwise everything will be full of uncertainty and confusion.

- PD 23. If you fight against all your sensations, you will have no standard to which to refer, and thus no means of judging even those sensations which you claim are false.

- PD 24. If you reject absolutely any single sensation without stopping to distinguish between opinion about things awaiting confirmation and that which is already confirmed to be present, whether in sensation or in feelings or in any application of intellect to the presentations, you will confuse the rest of your sensations by your groundless opinion and so you will reject every standard of truth. If in your ideas based upon opinion you hastily affirm as true all that awaits confirmation as well as that which does not, you will not avoid error, as you will be maintaining the entire basis for doubt in every judgment between correct and incorrect opinion.

- PD 25. If you do not on every occasion refer each of your actions to the ultimate end prescribed by nature, but instead of this in the act of choice or avoidance turn to some other end, your actions will not be consistent with your theories.

The takeaway from point three is: The Canonical faculties are our direct contact with our environment, and all inferential thinking (that is, all reasoning) depends on the accuracy of the data we get from the three canonical faculties. Truth is not revealed to us by contact with Platonic ideals (forms; divine revelations), nor can we derive truth based on logical calculations if the premises on which those calculations are based are not grounded in accurate observations through the canonical faculties.

To conclude this post, it’s interesting to note that Dictionary.com lists fifteen separate definitions, most of which are not at all what is referred to in the context of the Epicurean canon. A quick review of the list shows that only one (item five – standard; criterion) is reflective of Epicurean usage: