How To Live Like An Epicurean: The Example of Titus Pomponius Atticus

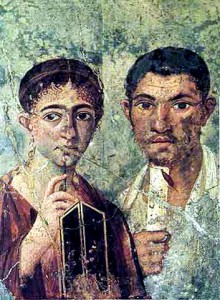

The question frequently arises, “How should one live today as an Epicurean?” Under the theory that there is really nothing new under the sun, among the best ways of answering that question is to look to see how those who claimed to be Epicureans lived in the ancient world. In addition to what we know about Epicurus from his biographers, and what we know about Lucretius’ life from his poem, we have another outstanding example from which there is much to learn: the life of Titus Pomponius Atticus.

The question frequently arises, “How should one live today as an Epicurean?” Under the theory that there is really nothing new under the sun, among the best ways of answering that question is to look to see how those who claimed to be Epicureans lived in the ancient world. In addition to what we know about Epicurus from his biographers, and what we know about Lucretius’ life from his poem, we have another outstanding example from which there is much to learn: the life of Titus Pomponius Atticus.

We know that Atticus was a devoted Epicurean from his correspondence with Cicero, but we also have left to us today the biography of Atticus written by Cornelius Nepos, a translation of which is available here and here from Epicurus.info. Nepos does not attribute Atticus’ achievements to his Epicureanism, but we can put two and two together and learn from the choices made by a devoted Epicurean who had available to him all of the important texts and access to the greatest Epicurean scholars of the time.

I will not reproduce the biography in full here, but highlight a number of significant aspects that Nepos recorded. In these comments we can derive traits of character which are timeless, which apply today as well as two thousand years ago, and which most of all derive directly from the application of Epicurean principles:

- In the boy, too, besides docility of disposition, there was great sweetness of voice, so that he not only imbibed rapidly what was taught him, but repeated it extremely well. He was in consequence distinguished among his companions in his boyhood, and shone forth with more lustre than his noble fellow-students could patiently bear; hence he stirred them all to new exertions by his application.

- Here [Athens] he lived in such a manner, that he was deservedly much beloved by all the Athenians; for, in addition to his interest, which was great for so young a man, he relieved their public exigencies from his own property; since, when the government was obliged to borrow money, and had no fair offer of it, he always came to their aid, and in such a way, that he never received any interest of them, and never allowed them to be indebted to him longer than had been agreed upon; both which modes of acting were for their advantage, for he neither suffered their debt to grow old upon them, nor to be increased by an accumulation of interest.

- He also conducted himself in such a way, that he appeared familiar with the lowest, though on a level with the highest.

- As long as he was among them, he prevented any statue from being erected to him; but when absent, he could not hinder it; and they accordingly raised several statues both to him and (?) Pilia, in the most sacred places, for, in their whole management of the state, they took him for their agent and adviser.

- When Sulla arrived at Athens in his journey from Asia, he kept Pomponius in his company as long as he remained there, being charmed with the young man’s politeness and knowledge; for he spoke Greek so well that he might have been thought to have been born at Athens; while there was such agreeableness in his Latin style, as to make it evident that the graces of it were natural, not acquired. He also recited verses, both in Greek and Latin, in so pleasing a manner that nothing could have been added to its attractions.

- Though he resided at Athens many years, paying such attention to his property as a not unthrifty father of a family ought to pay, and devoting all the rest of his time either to literature or to the public affairs of the Athenians, he nevertheless afforded his services to his friends at Rome; for he used to come to their elections, and whatever important business of theirs was brought forward, he was never found wanting on the occasion. Thus he showed a singular fidelity to Cicero in all his perils….

- He had an uncle, Quintus Caecilius, a Roman knight, an intimate friend of Lucius Lucullus, a rich man, but of a very morose temper, whose peevishness he bore so meekly, that he retained without interruption, to the extremity of old age, the good will of a person whom no one else could endure.

- …[H]e succeeded in effecting what was most difficult, namely, that no enmity should occur between those [Cicero and Hortensius] between whom there was emulation for such eminence, and that he himself should be the bond of union between such great men.

- He conducted himself in such a manner in political affairs, that he always was, and always was thought to be, on the best side; yet he did not mingle in civil tumults, because he thought that those who had plunged into them were not more under their own control than those who were tossed by the waves of the sea. He aimed at no offices (though they were open to him as well through his influence as through his high standing), since they could neither be sought in the ancient method, nor be gained without violating the laws in the midst of such unrestrained extravagance of bribery, nor be exercised for the good of the country without danger in so corrupt a state of the public morals. He never went to a public sale, nor ever became surety or contractor in any department of the public revenue. He accused no one, either in his own name or as a subscriber to an accusation. He never went to law about property of his own, nor was ever concerned in a trial. Offers of places, under several consuls and praetors, he received in such a way as never to follow any one into his province, being content with the honour, and not solicitous to make any addition to his property; …. In such conduct he consulted not only his dignity but his quiet; since he avoided even the suspicion of evil practices. Hence it happened that attentions received from him were more valued by all, as they saw that they were attributable to kindness, not to fear or hope.

- Thus he neither paid greater court to Antonius when in power, nor deserted those that were in desperate circumstances.

- Next followed the war that was carried on at Mutina, in which, if I were only to say that he was wise, I should say less of him than I ought; for he rather proved himself divine, if a constant goodness of nature, which is neither increased nor diminished by the events of fortune, may be called divinity.

- … Even when she [Fulvia] had bought an estate, in her prosperous circumstances, to be paid for by a certain day, and was unable after her reverse of fortune to borrow money to discharge the debt, he came to her aid, and lent her the money without interest, and without requiring any security for the repayment, thinking it the greatest gain to be found grateful and obliging, and to show, at the same time, that it was his practice to be a friend, not to fortune but to men….

- But he gradually incurred blame from some of the nobles, because he did not seem to have sufficient hatred towards bad citizens. Being under the guidance of his own judgment, however, he considered rather what it was right for him to do, than what others would commend.

- Thus Atticus, in a time of the greatest alarm, was able to save, not only himself, but him whom he held most dear; for he did not seek aid from any one for the sake of his own security only, but in conjunction with his friend; so that it might appear that he wished to endure no kind of fortune apart from him. But if a pilot is extolled with the greatest praise, who saves a ship from a tempest in the midst of a rocky sea, why should not his prudence be thought of the highest character, who arrives at safety through so many and so violent civil tumults?

- When he had delivered himself from these troubles, he had no other care than to assist as many persons as possible, by whatever means he could.

- One point we would wish to be understood, that his generosity was not timeserving or artful, as may be judged from the circumstances and period in which it was shown; for he did not court the prosperous, but was always ready to succour the distressed.

- Indulging his liberality in such a manner, he incurred no enmities, since he neither injured any one, nor was he, if he received any injury, more willing to resent than to forget it. Kindnesses that he received he kept in perpetual remembrance; but such as he himself conferred, he remembered only so long as he who had received them was grateful. He accordingly made it appear, to have been truly said, that “Every man’s manners make his fortune.” Yet he did not study his fortune before he formed himself, taking care that he might not justly suffer for any part of his conduct.

- …He was so far from coveting money, that he never made use of that interest except to save his friends from danger or trouble…

- But it was well known that the friends of Atticus, in times of danger, were not less his care in their absence than when they were present.

- Nor was he considered less deserving as a master of a family than as a member of the state; for though he was very rich, no man was less addicted to buying or building than he. Yet he lived in very good style, and had everything of the best….

- He kept an establishment of slaves of the best kind, if we were to judge of it by its utility, but if by its external show, scarcely coming up to mediocrity; for there were in it well-taught youths, excellent readers, and numerous transcribers of books, insomuch that there was not even a footman that could not act in either of those capacities extremely well. Other kinds of artificers, also, such as domestic necessities require, were very good there, yet he had no one among them that was not born and instructed in his house; all which particulars are proofs, not only of his self-restraint, but of his attention to his affairs; for not to desire inordinately what he sees desired by many, gives proof of a man’s moderation; and to procure what he requires by labour rather than by purchase, manifests no small exertion.

- Atticus was elegant, not magnificent; polished, not extravagant; he studied, with all possible care, neatness, and not profusion. His household furniture was moderate, not superabundant, but so that it could not be considered as remarkable in either respect.

- At his banquets no one ever heard any other entertainment for the ears than a reader; an entertainment which we, for our parts, think in the highest degree pleasing; nor was there ever a supper at his house without reading of some kind, that the guests might find their intellect gratified no less than their appetite, for he used to invite people whose tastes were not at variance with his own.

- After a large addition, too, was made to his property, he made no change in his daily arrangements, or usual way of life, and exhibited such moderation, that he neither lived unhandsomely, with a fortune of two million sestertii, which he had inherited from his father, nor did he, when he had a fortune of ten million sestertii, adopt a more splendid mode of living than that with which he had commenced, but kept himself at an equal elevation in both states.

- He had no gardens, no expensive suburban or maritime villa, nor any farm except those at Ardea and Nomentum; and his whole revenue arose from his property in Epirus and at Rome. Hence it may be seen that he was accustomed to estimate the worth of money, not by the quantity of it, but by the mode in which it was used.

- He would neither utter a falsehood himself, nor could he endure it in others. His courtesies, accordingly, were paid with a strict regard to veracity, just as his gravity was mingled with affability; so that it is hard to determine whether his friends’ reverence or love for him were the greater.

- Whatever he was asked to do, he did not promise without solemnity, for he thought it the part, not of a liberal, but of a light-minded man, to promise what he would be unable to perform. But in striving to effect what he had once engaged to do, he used to take so much pains, that he seemed to be engaged, not in an affair entrusted to him, but in his own. Of a matter which he had once taken in hand, he was never weary; for he thought his reputation, than which he held nothing more dear, concerned in the accomplishment of it. Hence it happened that he managed all the commissions of the Ciceros, Marcus Cato, Quintus Hortensius, Aulus Torquatus, and of many Roman knights besides. It may therefore be thought certain that he declined business of state, not from indolence, but from judgment.

- Of the affectionate disposition of Atticus towards his relatives, why should I say much, since I myself heard him proudly assert, and with truth, at the funeral of his mother, whom he buried at the age of ninety, that “he had never had occasion to be reconciled to his mother,” and that “he had never been at all at variance with his sister,” who was nearly of the same age with himself; a proof that either no cause of complaint had happened between them, or that he was a person of such kind feelings towards his relatives, as to think it an impiety to be offended with those whom he ought to love. Nor did he act thus from nature alone, though we all obey her, but from knowledge; for he had fixed in his mind the precepts of the greatest philosophers, so as to use them for the direction of his life, and not merely for ostentation.

- He was also a strict imitator of the customs of our ancestors, and a lover of antiquity, of which he had so exact a knowledge, that he has illustrated it throughout in the book in which he has characterized the Roman magistrates; for there is no law, or peace, or war, or illustrious action of the Roman people, which is not recorded in it at its proper period….

- He attempted also poetry, in order, we suppose, that he might not be without experience of the pleasure of writing it….

- After he had completed, in such a course of life, seventy-seven years, and had advanced, not less in dignity, than in favour and fortune (for he obtained many legacies on no other account than his goodness of disposition), and had also been in the enjoyment of so happy a state of health, that he had wanted no medicine for thirty years,he contracted a disorder of which at first both himself and the physicians thought lightly, for they supposed it to be a dysentery, and speedy and easy remedies were proposed for it; 3 but after he had passed three months under it without any pain, except what he suffered from the means adopted for his cure, such force of the disease fell into the one intestine, that at last a putrid ulcer broke out through his loins. Before this took place, and when he found that the pain was daily increasing, and that fever was superadded, he caused his son-in-law Agrippa to be called to him, and with him Lucius Cornelius Balbus and Sextus Peducaeus. When he saw that they were come, he said, as he supported himself on his elbow, “How much care and diligence I have employed to restore my health on this occasion, there is no necessity for me to state at large, since I have yourselves as witneses; and since I have, as I hope, satisfied you, that I have left nothing undone that seemed likely to cure me, it remains that I consult for myself. Of this feeling on my part I had no wish that you should be ignorant; for I have determined on ceasing to feed the disease; as, by the food and drink that I have taken during the last few days, I have prolonged life only so as to increase my pains without hope of recovery. I therefore entreat you, in the first place, to give your approbation to my resolution, and in the next, not to labour in vain by endeavouring to dissuade me from executing it.” Having delivered this address with so much steadiness of voice and countenance, that he seemed to be removing, not out of life, but out of one house into another,- when Agrippa, weeping over him and kissing him, entreated and conjured him “not to accelerate that which nature herself would bring, and, since he might live some time longer, to preserve his life for himself and his friends,”- he put a stop to his prayers, by an obstinate silence. After he had accordingly abstained from food for two days, the fever suddenly left him, and the disease began to be less oppressive. He persisted, nevertheless, in executing his purpose; and in consequence, on the fifth day after he had fixed his resolution, and on the last day of March, in the consulship of Cnaeus Domitius and Caius Sosius [ 32 B.C. ], he died. His body was carried out of his house on a small couch, as he himself had directed, without any funereal pomp, all the respectable portion of the people attending, and a vast crowd of the populace. He was buried close by the Appian Way, at the fifth milestone from the city, in the sepulchre of his uncle Quintus Caecilius.