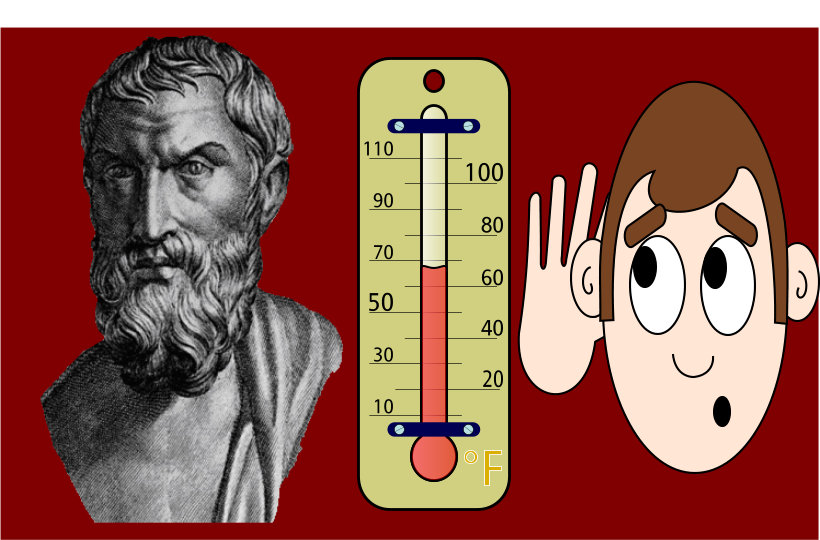

Can’t You Hear That This Thermometer Is Wrong?

Epicurus is often accused of holding that “all sensations are true,” but Norman Dewitt has exhaustively shown through numerous Epicurean texts that Epicurus knew very well that sensations cannot be judged to give a complete picture before analyzing them for accuracy. What Epicurus did say was that the senses report to us without injecting opinion of their own, and in that sense they are honest and not influenced by passion or prejudice.

More importantly for our present discussion, Epicurus held that the sensations are masters of their own domain. Diogenes Laertius records it this way:

Every sensation, he says, is devoid of reason and incapable of memory; for neither is it self-caused nor, regarded as having an external cause, can it add anything thereto or take anything therefrom. Nor is there anything which can refute sensations or convict them of error: one sensation cannot convict another and kindred sensation, for they are equally valid; nor can one sensation refute another which is not kindred but heterogeneous, for the objects which the two senses judge are not the same; nor again can reason refute them, for reason is wholly dependent on sensation; nor can one sense refute another, since we pay equal heed to all. And the reality of separate perceptions guarantees the truth of our senses. (Diogenes Laertius Book X, Line 31)

Lucretius recorded the same observation more emphatically:

Again, if any one thinks that nothing is known, he knows not whether that can be known either, since he admits that he knows nothing. Against him then I will refrain from joining issue, who plants himself with his head in the place of his feet. And yet were I to grant that he knows this too, yet I would ask this one question; since he has never before seen any truth in things, whence does he know what is knowing, and not knowing each in turn, what thing has begotten the concept of the true and the false, what thing has proved that the doubtful differs from the certain? You will find that the concept of the true is begotten first from the senses, and that the senses cannot be gainsaid. For something must be found with a greater surety, which can of its own authority refute the false by the true. Next then, what must be held to be of greater surety than sense? Will reason, sprung from false sensation, avail to speak against the senses, when it is wholly sprung from the senses? For unless they are true, all reason too becomes false. Or will the ears be able to pass judgement on the eyes, or touch on the ears? or again will the taste in the mouth refute this touch; will the nostrils disprove it, or the eyes show it false? It is not so, I trow. For each sense has its faculty set apart, each its own power, and so it must needs be that we perceive in one way what is soft or cold or hot, and in another the diverse colours of things, and see all that goes along with colour. Likewise, the taste of the mouth has its power apart; in one way smells arise, in another sounds. And so it must needs be that one sense cannot prove another false. Nor again will they be able to pass judgement on themselves, since equal trust must at all times be placed in them. (Lucretius Book IV – Bailey)

The relevance of these to our topic question is this: You cannot determine that a thermometer is incorrect by hearing it. The ears by listening have no ability to second-guess the thermometer.

More profoundly, not only can the ears not second-guess the eyes or the sense of touch, neither “logic” or “reason,” acting alone, can second-guess any of the senses. As already stated above in Diogenes Laertius, “nor again can reason refute them, for reason is wholly dependent on sensation…”

Again, and with greater emphasis, by Lucretius:

And if reason is unable to unravel the cause, why those things which close at hand were square, are seen round from a distance, still it is better through lack of reasoning to be at fault in accounting for the causes of either shape, rather than to let things clear seen slip abroad from your grasp, and to assail the grounds of belief, and to pluck up the whole foundations on which life and existence rest. For not only would all reasoning fall away; life itself too would collapse straightway, unless you chose to trust the senses, and avoid headlong spots and all other things of this kind which must be shunned, and to make for what is opposite to these. Know, then, that all this is but an empty store of words, which has been drawn up and arrayed against the senses. Again, just as in a building, if the first ruler is awry, and if the square is wrong and out of the straight lines, if the level sags a whit in any place, it must needs be that the whole structure will be made faulty and crooked, all awry, bulging, leaning forwards or backwards, and out of harmony, so that some parts seem already to long to fall, or do fall, all betrayed by the first wrong measurements; even so then your reasoning of things must be awry and false, which all springs from false senses.

These observations have an even more profound implication. Just as reason or logic alone cannot second-guess any of the senses, reason and logic alone cannot second-guess the sense of pain and pleasure.

Much angst, and the entire philosophy known as “stoicism,” has been wasted in a futile effort to reject this point. The anti-Epicurean philosophers assert innumerable arguments why some pleasures may be more worthy than others, or more virtuous than others, or more noble than others, or (if they are eclectics), simply better than others – whatever that means. But every one of these distinctions is artificial and arbitrary, and “more worthy” or “more virtuous” or “more noble” has no more definition that the hopeless “better.”

Just as hearing cannot second-guess hearing, there is no faculty given to us by Nature than can second-guess pleasure and pain. If a thing or an activity is reported to us as pleasurable, there is no second-guessing the sensation of pleasure any more than second-guessing the scent of a rose. A sensation of pleasure may be incomplete; it may be distorted; it may be unreliable to the full picture of what is going on at the moment. Nevertheless, like any other sensation, pleasure and pain are reported to us honestly, and these sensations are entitled to as much respect as the eyes or ears, or the respect we would afford in court to any honest witness whose testimony may nevertheless not be accurate to the facts in full and in every respect.

Thus we see that pleasure, being a reporting faculty that is king of its own domain, cannot be judged as by reason or logic as worthy or unworthy, virtuous or unvirtuous, noble or ignoble. Pleasure is whatever our faculty of pleasure reports to us is pleasing, just as pain is whatever our faculty of pain reports to us is painful. “Hence Epicurus refuses to admit any necessity for argument or discussion to prove that pleasure is desirable and pain to be avoided. These facts, be thinks, are perceived by the senses, as that fire is hot, snow white, honey sweet, none of which things need be proved by elaborate argument: it is enough merely to draw attention to them.” [Cicero’s Torquatus in On Ends]

As Epicurus explains to us in the letter to Menoeceus, and as every normal adult knows and understands, the wise man does not choose every pleasure and avoid every pain. But every normal adult does not know and understand the real basis for this choice and avoidance, and a proper foundation for this reasoning is critical to living happily. We do not and cannot make out decisions in life based solely on calculations of reason or logic or divine revelation as to what is worthy, virtuous, noble, or godlike. If we wish to live according to Nature, rather than by our own arbitrary whims, then we must make our decisions ONLY on the basis of whether the result will in the final result be greater pleasure or greater pain:

And since pleasure is our first and native good, for that reason we do not choose every pleasure whatsoever, but will often pass over many pleasures when a greater annoyance ensues from them. And often we consider pains superior to pleasures when submission to the pains for a long time brings us as a consequence a greater pleasure. While therefore all pleasure because it is naturally akin to us is good, not all pleasure is should be chosen, just as all pain is an evil and yet not all pain is to be shunned. It is, however, by measuring one against another, and by looking at the conveniences and inconveniences, that all these matters must be judged. Sometimes we treat the good as an evil, and the evil, on the contrary, as a good.

That word ONLY cannot be emphasized enough. No matter what our background – religious, secular, deist, atheist, humanist – we have all been taught that there is some perspective or standard which is superior to the faculty of pleasure and pain. We have been browbeaten into believing that our minds or our gods create standards which are as valid — in fact more valid — than those given to us by Nature. The truth is that the Earth is not the center of the Universe and men are not a mystical creature with supernatural exemptions from the laws of Nature. The ONLY faculty given to humans as an ultimate criteria for living – the only faculty given to dogs or cats or any other living creature – is the faculty of pleasure and pain. Through our mental capacities we can succeed in living lives of happiness and pleasure beyond the conception of any other species, but no amount of logic and reason can give us the motive power that Nature gave us in the faculty of pain and pleasure. We often talk today as if we value and are in closer touch with Nature than those in ages past, but which of us really lives that closeness in which Lucretius saw Nature and her gift of Pleasure as –

[J]oy of men and gods, Venus the life-giver, who beneath the gliding stars of heaven fillest with life the sea that carries the ships and the land that bears the crops; for thanks to thee every tribe of living things is conceived, and comes forth to look upon the light of the sun. Thou, goddess, thou dost turn to flight the winds and the clouds of heaven, thou at thy coming; for thee earth, the quaint artificer, puts forth her sweet-scented flowers; for thee the levels of ocean smile, and the sky, its anger past, gleams with spreading light. For when once the face of the spring day is revealed and the teeming breeze of the west wind is loosed from prison and blows strong, first the birds in high heaven herald thee, goddess, and thine approach, their hearts thrilled with thy might. Then the tame beasts grow wild and bound over the fat pastures, and swim the racing rivers; so surely enchained by thy charm each follows thee in hot desire whither thou goest before to lead him on. Yea, through seas and mountains and tearing rivers and the leafy haunts of birds and verdant plains thou dost strike fond love into the hearts of all, and makest them in hot desire to renew the stock of their races, each after his own kind. … [T]hou alone art pilot to the nature of things, and nothing without thine aid comes forth into the bright coasts of light, nor waxes glad nor lovely,

Rather than study and follow Nature, men have invented for themselves arbitrary standards and wandered all over the spectrum from conspicuous consumption luxury to self-flagellation asceticism. What unites religionists and false philosophers in error is their rebellion against Nature. As a result forms of hypocritical asceticism which condemn pleasure and extol pain have dominated much of history — at least officially, and at least as preached to the masses of men. The overclasses have always found a way to indulge in pleasure, while preaching to the lower classes the virtues of “simplicity” that allow the overclasses themselves to enjoy what they condemn in others. But Epicurus was equally clear in condemning both excessive luxury and excessive simplicity:

63. There is also a limit in simple living, and he who fails to understand this falls into an error as great as that of the man who gives way to extravagance.

The bottom line is this: pleasure is that which is pleasing; pain is that which is painful. Our faculty of pleasure and pain can and will report to us such matters as forms and intensities and durations of pleasure. But there is no faculty of reason or logic or anything else that can assess for us that any pleasure is more worthy, or more virtuous, or more godlike than any other. Nature has given us one faculty by which to judge pleasure, and only one faculty. All pleasures are good, whether they be pleasures of action or pleasures of reflection, pleasures of luxury or pleasures of simplicity, pleasures of what some people consider depraved, or pleasures of what other people consider holy. No pleasure is a bad thing in itself, but the things which produce certain pleasures entail disturbances many times greater than the pleasures themselves. (Doctrine 8)

It is up to us to use our minds and other resources intelligently so as to understand the consequences of our actions. If we engage in an activity that we find pleasurable, but the result of that activity is an early death, or a mob out to lynch us because we engaged in it, then we must assess that probable reaction and decide whether it is truly worth the effort.

Above all, Epicurus advised us to steer clear of doubt and confusion. Do not look to the heavens, do not look to luxury, do not look to simplicity, do not look to action, do not look to contemplation. Look only to the ultimate end of Nature, the only leader that Nature gave us – to divine pleasure, guide of life – and apply that end to your own unique and particular circumstances.

And if we fail to heed that advise? If we give in to thinking that our efforts at simplicity, at asceticism, at introspection, at reflection, at logic, at reason, or at pleasing “the gods” will lead to something “higher” or “better”? Then we have not one but two doctrines from Epicurus to describe what will happen:

PD 22. We must consider both the ultimate end and all clear sensory evidence, to which we refer our opinions; for otherwise everything will be full of uncertainty and confusion.

PD 23. If you fight against all your sensations, you will have no standard to which to refer, and thus no means of judging even those sensations which you claim are false.

__________________________

Addendum: Just to add another comment as a summary of the original post, I think this formulation may be helpful: The general meaning of both PD3 and the comments on the height of pleasure is probably: “Any pleasure is at its natural limit when it is undiluted by any pain.”

This is an extremely critical statement for establishing that pleasure is a natural faculty qualifies as the guide of life. It is essential because it refutes those who argue that pleasure cannot be used as a reliable guide because pleasure is always capable of increase. But it is a statement of pleasure in its role as a guiding sensation that applies to innumerable experiences in innumerable different ways. The statement does not otherwise identify the pleasure or pleasures being experienced. It says nothing about the type, quality, duration, or any other aspect of the positive sensation of pleasure being measured. That is why “absence of pain” tells you next to nothing about the pleasurable experience being measured. It tells you one thing only: that whatever the experience of pleasure is – it is not accompanied by pain.

The experience of a healthy child lying on his back on sailboat, looking at sky, and clearing his mind of all trouble can well described as undiluted pleasure. The experience of Neil Armstrong, after spending a lifetime of working for the experience, setting foot on the moon for the first time was also likely an experience of undiluted pleasure, even euphoria. Both experiences were undiluted by pain and can be considered pleasure at its limit. But in virtually every other respect the two experiences are totally different. Both experiences are good and both experiences are desirable, but it would be a major mistake – even ridiculous – to consider them as the same.