A Pattern I Observe In The Connection (Or Lack Thereof) Between Humanism And Epicurean Philosophy

By Cassius Amicus Published Against Platonism

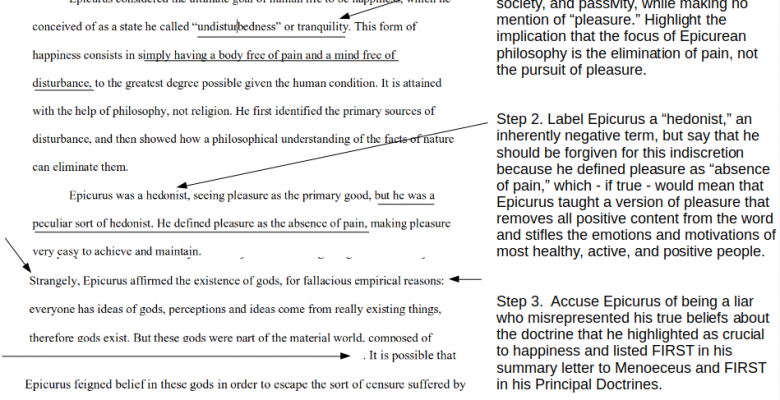

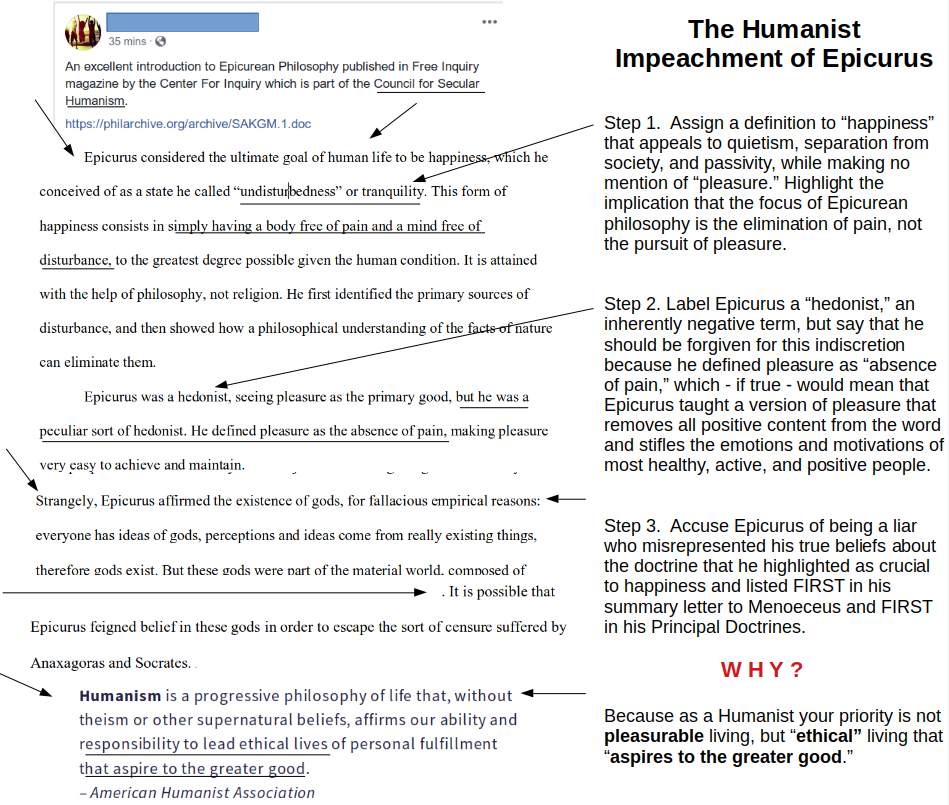

My goal in the discussion of “Humanism” is to generate “light” rather than “heat,” but since the goal of life is “light” (pleasure), and not the avoidance of “heat” (pain), I have more to add beyond what I recently posted on Epicureanfriends.com. The accompanying graphic is not a “proof” of anything. It is simply a summary of my observation, over many years, of a common thread that binds what I find to be the majority view of “Humanism” to what I find to be a popular but flawed view of Epicurus.

The text on the left is from an article that just came to my attention. It is what is often considered to be a “good” article about Epicurus. However the version of Epicurus that it promotes, I submit, is not a version that Epicurus would recognize or endorse, and not only because he would not appreciate being called a liar.

I certainly understand that many people will disagree with my commentary on the right. Everyone has to evaluate for themselves whether this pattern and connection really exists, and their own view of it.

After posting the above graphic I was reminded of PD5 as another example of how a Humanist might reach the same conclusion. My reply was:

After posting the above graphic I was reminded of PD5 as another example of how a Humanist might reach the same conclusion. My reply was:

Yes, that’s the problem with reading PD5 out of context. If one had first started with the twelve fundamental principles of physics, one would know that eternal absolute rules are physically impossible due to the nature of the universe (no center, no creating god, constant motion, all things that come together eventually break apart).

If one had read more of the ethics, one would have read the argument (now mainly left to us in Torquatus / Cicero) that all virtue is subservient to the goal of pleasure, and thus has no absolute meaning outside of the context of the goal of pleasure.

And if one had read more of the epistemology, one would know that Epicurus held the senses, feelings, anticipations (all human “relative” and not “absolute” faculties) to be the source of and test of all knowledge, and would therefore know that morality requires context, and that rationalist morality is false and a dead end.

But it is absolutely right to ask about PD5 – read it out of context and it is easy to conclude that Epicurus was talking in terms of OUR modern philosophical system (essentially a Stoic /Platonic / Aristotelian mashup), instead of talking in terms of his own system. And if you do presume he’s talking in our context, you draw exactly the opposite conclusion rather than the conclusion that is inherent in Epicurus’ own system.

In the same way, it is easy to read one passage in the letter to Menoeceus and conclude that “absence of pain” is the full and complete definition of pleasure – despite everything else Epicurus said about joy and dance and food and sex and almost every other kind of normal pleasure that no one in his right mind would think to call “absence of pain.”

“Gee honey, you really gave me a lot of “absence of pain” in bed tonight!!!” Such a person deserves to be slapped, not given a philosophy degree.

The basic issue is that Epicurean philosophy requires an attitude of understanding and applying the concept of “context.”

Continuing onward:

The crucial sentence in the analysis of the Humanist article quoted above is this one: “He [Epicurus] defined pleasure as the absence of pain.”

“He defined pleasure as the absence of pain.” This is the sleight of hand you see in some form or another in all of the “anesthesia” analysts. But is this true?

The implication of this statement is that Epicurus considered “pleasure” and “absence of pain” to be exact equivalents – interchangeable terms – the same in every respect. Such a statement, if that is what Epicurus meant, would in fact be shocking, and would be in fact the centerpiece of the philosophy, as this Humanist claims it to be. But what is the evidence for that?

Where can this definition be found to be explicitly stated in Lucretius, Epicurus’ faithful poet and renderer of Epicurus’ own “On Nature?”

Where can this definition be found in the list of “Authorized Doctrines” which was clearly represented to be the summation of the most important points of the philosopher? Or in the later iteration of that document in the form of the Vatican Sayings?

Nowhere do words appear to the effect that “absence of pain” and “pleasure” are interchangeable terms, and in fact Epicurus himself does not use those terms that way even in his own letters, even within the letter to Menoecues.

The key to unwinding this is to observe what is said within the Principal Doctrines, in the form of Doctrine Three, which reads (Bailey translation) “The limit of quantify of pleasures is the removal of all that is painful.” This is joined with the explanation that “Wherever pleasure is present, so long as it is there, there is neither pain of body or of mind, nor of both at once.”

Epicurus does not say that “pleasure” and “absence of pain” are the same except in ONE respect: *Quantity of Experience.”

The explanation for the importance of the limit in “Quantity of experience of pleasure” is the Platonic argument in Philebus, repeated elsewhere, that any ultimate and final good, in order to be considered “highest,” must have a limit – must not be improvable by the addition of something else, or of “more.” And Epicurus’ response to that argument is that the most pleasurable life that it is possible for any being to experience is one in which ALL of that being’s experience was filled with pleasure — “filled” meaning that it contains no mixture of pain.

In order to establish that point it was necessary for Epicurus to stress that ALL experience is one of either of two kinds – pleasure or pain. And when seen from that perspective, the quantity of one measures the same as the “absence of” the other, just as the quantity of gasoline in your car’s tank can be described as that part of the tank which is “absent of air.”

Turning back to the letter of Menoeceus, this overall perspective can be used to explain the passages that otherwise are apparently inconsistent to the point of being otherwise nonsensical.

In what follows I am referring to the Bailey translation.

First remember that “all good and evil consists in sensation” – this being a reference to the feeling of either pleasure or pain evoked in any sensation of feeling.

The paragraph that begins “We must consider that of desires some are natural, others vain….” occupies within the letter the approximate position – after discussion of gods, and of death, as does Principal Doctrine three in the Authorized List. This positioning in itself is evidence that the emphasis is on quantity, not full equivalence.

This paragraph contains a series of statements such as “when we do not feel pain, we have no need of pleasure” that would seem to call for Epicurus to conclude that “avoiding pain” is the most important thing in life. Indeed Epicurus says in this passage that “For it is to obtain this end that we always act, namely, to avoid pain and fear. ” But does Epicurus close the passage by saying that “And for this we call ‘absence of pain’ or ‘freedom from pain” the beginning and end of the blessed life”? No!

The true conclusion of the paragraph is “And for this we call PLEASURE the beginning and end of the blessed life. Why the switch back to “pleasure”? Because Epicurus never consider the two terms to be exact equivalents. Every bit of this paragraph can be read to mean: “The goal of life – the highest life – is one filled with pleasure and without any pain. Only when our experience is NOT filled with pleasures, only when some degree of pain is present, do we need MORE pleasure. Because when we reach the goal, the definition which we are concerned about, we have by definition filled our experience totally with pleasurable experiences, and succeeded in eliminating painful experiences. We have no MORE need of pleasurable experiences when we are full of pleasures, any more than we have need of MORE gasoline when our gas tanks remain completely full of gasoline for the life of the car.

The next two paragraphs (“And since pleasure is the first good….” and “And again independence of desire….” emphasize that we sometimes choose pain for a time when that choice leads to greater overall pleasure — a greater TOTAL EXPERIENCE OF PLEASURE over the lifetime. Once again, there is NO INFERENCE that “pleasure” and “absence of pain” are expressions that are equivalent in every respect.

Now we turn to “When therefore, we maintain that pleasure is the end….” we find “we do not mean the pleasure of profligates….” but freedom from pain in the body and from trouble in the mind.” Then the next sentence focuses on the means of production of produc[ing] the pleasant life.

There is absolutely nothing in that paragraph inconsistent with the interpretation that Epicurus is again referring to “the end” and “the pleasant life” as the life which is FULL OF PLEASURABLE EXPERIENCES as the term “pleasure” is ordinarily understood. He is simply saying that the most efficient way of producing a life which is as full of pleasurable experiences as possible is not by rushing headlong for immediate pleasures, but by prudently calculating the results of our actions before taking them so that we maximize the experience of pleasure and minimize the experience of pain.

And indeed Epicurus goes further to emphasis that he is describing the conceptual goal of a life full of pleasure – a life which can be described as reaching “the limit of pleasure” when he says “For example who, think you, is better than the man….. [who implements Epicurean philosophy]?

This indeed is so clearly defined as the goal of life that he equates it at the end of the letter with reaching the result of being “a god among men” — which in Epicurean terminology is not something supernatural or non-natural, but implies a state which cannot be exceeded.

This same state which cannot be exceeded is shown to be full of pleasures as ordinarily defined in the more extensive passage delivered by Torquatus:

“The truth of the position that pleasure is the ultimate good will most readily appear from the following illustration. Let us imagine a man living in the continuous enjoyment of numerous and vivid pleasures alike of body and of mind, undisturbed either by the presence or by the prospect of pain: what possible state of existence could we describe as being more excellent or more desirable? One so situated must possess in the first place a strength of mind that is proof against all fear of death or of pain; he will know that death means complete unconsciousness, and that pain is generally light if long and short if strong, so that its intensity is compensated by brief duration and its continuance by diminishing severity. Let such a man moreover have no dread of any supernatural power; let him never suffer the pleasures of the past to fade away, but constantly renew their enjoyment in recollection, and his lot will be one which will not admit of further improvement.”

In sum, the above analysis is what is going on with the discussion of “Absence of pain” in the letter to Menoeceus. It is absolutely untrue of Epicurus to say, as does the Humanist writer, that “He defined pleasure as absence of pain.”

But the Humanist writer, or those whose essential focus is Humanism, are unlikely to reach the conclusion demanded by the full context of Epicurean philosophy because they do not wish to do so. Their goal is “an ethical life” that “aspires to the greater good.” That is Platonism – that is Aristotelianism – that is Stoicism – but it is certainly not Epicurean, and never the two will meet today, any more than they met during the lifetime of battles between these schools in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds.