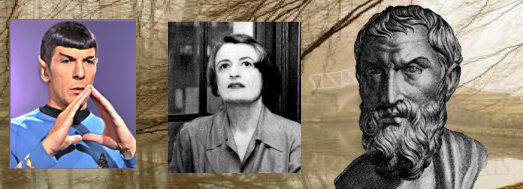

A Case Study in Failing to Appreciate the Scope of Epicurus’ Wisdom: Ayn Rand and the Objectivists

Casual readers are frequently attracted by Epicurus’ views on pleasure, on peace of mind, or on the requirements of living happily. Some are attracted by Epicurus’ understanding of the non-interference of gods in human affairs, or on the necessity of facing death boldly. Many such readers simply pick these flowers from Epicurus’ garden and go on their way, but in so doing they fail to appreciate the significance of the method by which these fruits were produced, and they deny themselves the full benefit of Epicurus’ wisdom. And sometimes the unfortunate results of such cherry-picking go far beyond the loss of the chance to experience greater happiness in life.

Several weeks ago (on 9/25/10) the owner of the Epicurus Facebook page posted a link to an article about Aristotle and Epicurus on a site largely devoted to the work of Ayn Rand. The responses to that entry led me to look further into the subject, and after some interesting research and even correspondence with a number of her devotees, I have composed this brief post on the dangers which confront those who adopt only a part of the ideas of Epicurus without understanding the full foundation from which they spring.

Ayn Rand was the American novelist, born in Russia, who wrote the well known novels “The Fountainhead” and “Atlas Shrugged.” In the 1960’s she founded a philosophy known as “Objectivism,” which she promoted until her death in 1982, and which her followers continue to promote to this day. Rand refused to credit anyone other than Aristotle for her philosophic inspiration, but even a cursory review of her work shows that in many respects her philosophy resembles a brew of Epicureanism mixed with Nietzscheism and a variety of other incompatible elements. This blog will not be sidetracked into an extensive discussion of Rand or Objectivism, but the unhappy later years of Ayn Rand and the years of internal schisms that have plagued her followers after her death provide a useful cautionary tale of the perils of too-narrow an appreciation for the wisdom of Epicurus.

There is much on the internet about the relationship between the ideas of Ayn Rand and those of Epicurus. The author of the internet article “Epicureanism after Epicurus” records in broad and overgeneralized terms:

Modern Epicureanism is regarded as an offshoot of Ayn Rand’s Objectivism. Whereas Epicurus stressed the importance of pleasure, Rand, inspired by Epicurus, tacked it on as an afterthought (she was actually quite Victorian in her ethical views). Epicureanism seems to have two strains — a “subjectivist” and an “objectivist” version. The former attracts lifestyle contrarians and taboo-challengers, while the latter attracts more tradition-minded intellectuals who indulge the occasional whim (something pure Objectivists would never tolerate). Whereas the “subjectivist” Epicureans are more sensualist and existentialist, the “objectivist” Epicureans tend to worship the New Agey psychological views of Nathaniel Brandon. The two camps are friendly to one another and both were inspired by Rand’s writings on egoism, rationality, and pleasure. [Note: this last sentence, that the two camps are “friendly to one another” is wildly inaccurate.]

Perhaps the most in-depth discussion of the unacknowledged influence of Epicurus on Ayn Rand is contained in the article ‘Epicurus and Rand’ which was published in 1995 in Volume 2, No. 3 of a publication devoted to the work of Ayn Rand entitled “Objectivity.” This article makes the statement:

If Epicurus is understood as the first conscious and consistent anti-Platonist, and if Rand is also interpreted as struggling chiefly against all modern variations of Platonism, then commonalities in Epicurean and Randian thought should not be surprising. While Epicurus and Rand are both philosophical system builders, their primary interest is in moral thought. Therefore the purpose of this essay is to demonstrate the existence of fundamental similarities between both metaethical and normative aspects of Epicurean and Randian ethics.

Much effort could be devoted to exploring the claims of these two sources, especially the article from Objectivity, which correctly cites DeWitt and lays out in clear detail how Rand mirrors Epicurus without acknowledging him. All we have time to do here, however, is to observe how Ayn Rand seems to have adopted a number of the same ideas as Epicurus, but failed to adopt others, or failed to pursue the ideas that she did adopt far enough. In failing to follow the insights which were plainly available to her through Epicurus, Rand laid the groundwork for both the personal crisis and depression she experienced in the later years of her life and the decades of bitter feuding that her followers have endured after her death.

One thing that struck me as I reviewed the publicly available material is that Rand and her followers frequently identify Plato as the arch-villain of philosophical history, but never seem to acknowledge that Thomas Jefferson, who credited Epicurus, made essentially the same observation over a hundred years prior to Rand. (See his 1819 letter to William Short which is featured on this and other Epicurean websites.)

But two other omissions are even more striking, and seem to have led directly to the downfall of Ayn Rand personally and to the bitter divisions between her supporters after her death:

(1) Rand does not appear to incorporate in her philosophy any equivalent to Epicurus’ identification of friendship as essential to happy living. As a result, Rand (or perhaps more accurately, her followers) worshiped individualism without recognizing the role of friendship or the contextual requirements of Nature in the shaping of those actions which are proper for the individual (see Doctrine 27 and Torquatus’ discussion of friendship in Cicero’s Defense of Epicurus).

(2) Rand seems to have personally violated Epicurus’ repeated warnings against the perils of unreasonable indulgence in the passions of romantic love. By elevating those passions far beyond any limit that Epicurus would have recognized as reasonable, she came close to ruining her own marriage and spawned years of apparent depression and regret. If only she had taken item 51 of the Vatican List to heart!

Rand’s failure to appreciate Epicurus’ instructions to value friendship, and to avoid the dangers of overindulging the passions of romantic love, led her to engage in an affair with her most prominent student of the time, Nathaniel Branden, as chronicled in his book Judgment Day. Just as Epicurus would have warned her, that affair led inevitably to bizarre arrangements between Rand and her husband, and eventually to a bitter split with Branden himself. At least in part because Rand had ignored Epicurus’ advice on friendship and on benevolent and gracious criticism in dealing with those who stray into error, Rand was unable to recover from the harm that the affair had caused. Her bitter denunciations of Branden and his allies, and the tone of harsh recrimination which she and her immediate followers set in the 1960’s, echo to this very day.

In the course of writing this blog entry I discussed these matters and corresponded via email with a number of long-time Objectivists who offered me their perspectives. They were kind enough to point me to Epicureanism after Epicurus, The Objectivity Article on Rand and Epicurus, and to a decades-old essay about the Branden-Rand split written from an Epicurean perspective, which has now been transcribed to the internet and updated with current links here. They also informed me that a history of the skirmishes within Objectivism can be found at a website devoted to nothing but Randian infighting (“ARIWatch”). A particularly revealing battle in this ongoing internal war — showing how the Objectivists are unable to relate to each other in friendship or to correct each other graciously and without acrimony when they differ — is recorded here in an article entitled “Anthemgate.”

Despite the many parallels that naturally arise when comparing two anti-Platonic philosophers, the divide between Ayn Rand and Epicurus is deep. Perhaps, as Rand claimed, Objectivism truly derives from Aristotle, and that she was never aware of the wisdom of Epicurus to which many aspects of her philosophy are superficially related. If so, the turmoil and unhappiness among these of Aristotle’s children is additional vindication of the view that the foundation of happy living can be found in Epicurus, and not in the Platonism or Aristotelianism which most people today believe are the only philosophical alternatives.