Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 231 Is Now Available

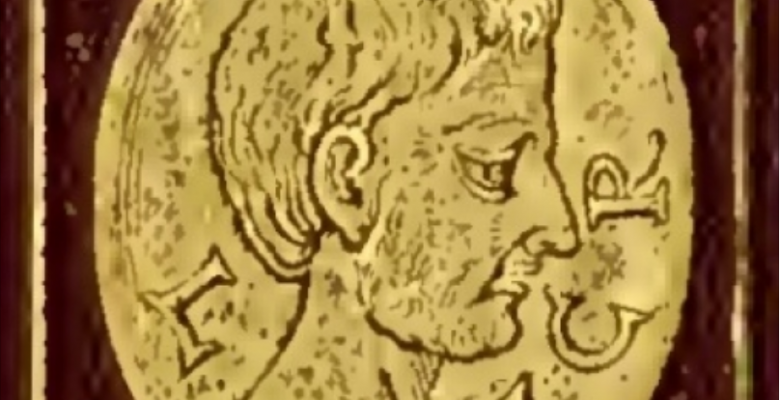

Welcome to Episode 231 of Lucretius Today. This is a podcast dedicated to the poet Lucretius, who wrote “On The Nature of Things,” the most complete presentation of Epicurean philosophy left to us from the ancient world.

Each week we walk you through the Epicurean texts, and we discuss how Epicurean philosophy can apply to you today. If you find the Epicurean worldview attractive, we invite you to join us in the study of Epicurus at EpicureanFriends.com.

For our new listeners, let me remind you of several ground rules for both our podcast and our forum.

First: Our aim is to bring you an accurate presentation of classical Epicurean philosophy as the ancient Epicureans understood it.

Second: We won’t be talking about modern political issues in this podcast. How you apply Epicurus in your own life is of course entirely up to you. We call this approach “Not Neo-Epicurean, But Epicurean.” Epicurean philosophy is a philosophy of its own, it’s not the same as Stoicism, Humanism, Buddhism, Taoism, Atheism, Libertarianism or Marxism – it is unique and must be understood on its own, not in terms of any conventional modern morality.

Third: One of the most important things to keep in mind is that the Epicureans often used words very differently than we do today. To the Epicureans, Gods were not omnipotent or omniscient, so Epicurean references to “Gods” do not mean at all the same thing as in major religions today. In the Epicurean theory of knowledge, all sensations are true, but that does not mean all opinions are true, but that the raw data reported by the senses is reported without the injection of opinion, as the opinion-making process takes place in the mind, where it is subject to mistakes, rather than in the senses. In Epicurean ethics, “Pleasure” refers not ONLY to sensory stimulation, but also to every experience of life which is not felt to be painful. The classical texts show that Epicurus was not focused on luxury, like some people say, but neither did he teach minimalism, as other people say. Epicurus taught that all experiences of life fall under one of two feelings – pleasure and pain – and those feelings — and not gods, idealism, or virtue – are the guides that Nature gave us by which to live. More than anything else, Epicurus taught that the universe is not supernatural in any way, and that means there’s no life after death, and any happiness we’ll ever have comes in THIS life, which is why it is so important not to waste time in confusion.

Today we are continuing to review the Epicurean sections of Cicero’s “On the Nature of The Gods,” as presented by the Epicurean spokesman Velleius, beginning at the end of Section 10.

For the main text we are using primarily the Yonge translation, available here. The text which we include in these posts is the Yonge version, the full version of which is here at Epicureanfriends. We will also refer to the public domain version of the Loeb series, which contains both Latin and English, as translated by H. Rackham.

Additional versions can be found here:

Frances Brooks 1896 translation at Online Library of Liberty

Lacus Curtius Edition (Rackham)

PDF Of Loeb Edition at Archive.org by Rackham

Gutenberg.org version by CD Yonge

A list of arguments presented will be maintained here.

Today’s Text

XII. Empedocles, who erred in many things, is most grossly mistaken in his notion of the Gods. He lays down four natures as divine, from which he thinks that all things were made. Yet it is evident that they have a beginning, that they decay, and that they are void of all sense.

Protagoras did not seem to have any idea of the real nature of the Gods; for he acknowledged that he was altogether ignorant whether there are or are not any, or what they are.

What shall I say of Democritus, who classes our images of objects, and their orbs, in the number of the Gods; as he does that principle through which those images appear and have their influence? He deifies likewise our knowledge and understanding. Is he not involved in a very great error? And because nothing continues always in the same state, he denies that anything is everlasting, does he not thereby entirely destroy the Deity, and make it impossible to form any opinion of him?

Diogenes of Apollonia looks upon the air to be a Deity. But what sense can the air have? or what divine form can be attributed to it?