“Failure of Nerve?” Or “Failure to Pay Attention?”

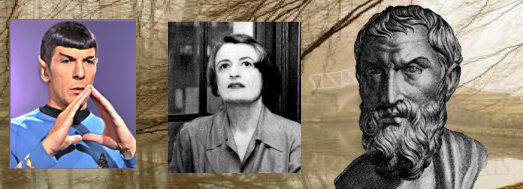

I have a standing rule for my blog that I will not devote more space than absolutely necessary to discussing Ayn Rand and Objectivism. That is not to say that the topic is uninteresting, but only to say that the purpose of this blog is to pursue a much more important and positive work: that of researching, discussing, and applying the true tenets of Epicurean philosophy. Several posts in the “Garden of Epicurus” Facebook page this week, however, have prompted me to suspend my rule for two posts:

The first post (this one) is regrettably negative, but it is required to defend the reputation of Epicurus against a jarringly-inaccurate misrepresentation of his true views.

The second post (soon to come) is happily positive, and will highlight an outstanding essay by Peter St. Andre. As with all of Peter’s excellent work, the essay to be discussed is highly useful on its own terms. Its relevance here is that it develops a fascinating point by examining the Epicurean framework of a crucial aspect of the work of both Nietzsche and Rand.

Now to the first post:

The Facebook discussion had to do with the delay that some experience in “finding” Epicurus when their philosophical interests happened to have begun with the works of Ayn Rand. Most who read this blog presumably have no such issue, but some readers (particularly overseas) might not be aware of the situation, and some knowledge of it might prove useful to them.

During her lifetime Ayn Rand sought to minimize recognition of the influence that Nietzsche played in the development her philosophy. Similarly, it is Randian orthodoxy that the only Greek philosopher worthy of admiration is Aristotle. Even though much of Rand’s own philosophy is grounded in opposition to Platonism, she denies any credit whatsoever to the ideas of the premier Anti-Platonist of them all: Epicurus.

Ayn Rand herself, because of her admitted study of Nietzsche, could not have failed to have been aware of the merit of Epicurus. As a friend and fellow fan of Epicurus from Eastern Europe posted recently, among Nietzche’s many references to Epicurus was: “Eternal Epicurus – Epicurus has always lived and still lives today, unknown to those who called and call themselves Epicureans, and of no renown among philosophers. He has his own name forgotten: that was the heaviest burden that he has ever thrown away.” – Freidrich Nietzsche, The Wanderer, II, 227

I gather that in the “early years” of her movement, Rand may have given Epicurus more recognition, and indeed today there are significant articles available on the internet which discuss Epicurus in an Objectivist context. But today, some thirty years after her death, Rand’s decision to ignore Epicurus has led to shocking degree of misinformation that is now dominant among too many of her modern followers.

Exhibit one in support this observation is the latest work of Rand’s “intellectual heir,” Leonard Peikoff. Peikoff has just published a book entitled “The DIM Hypothesis,” which is in large part a survey of the history of philosophy, for the purpose of dividing it up into categories according to whether the influence of Plato, Kant, or Aristotle was or is paramount. In this new book it appears that the name “Epicurus” does not appear a single time. “Lucretius” is apparently mentioned twice, but without any reference to his relationship to Epicureanism!

Exhibit two in support of this post can be found in the Leonard Peikoff question-answer podcasts available on his web page, specifically the podcast of February 9, 2009 which can be found by searching “Stoicism” on his site. The following is a rough (but I think accurate) transcription of the relevant part, with Peikoff giving his opinion in response to a general question about Stoicism and Epicurus:

I’d appreciate your opinion on Stoicism. Stoicism is the ancient philosophy which comes down in essence to… they believe in an all-powerful god who predestines all events for the best, and they believe that in order to avoid failure and suffering in this life you should stop valuing anything. That’s what the idea of being “Stoic” was – give up all desires so that no matter what happens you can’t be hurt. The idea was “nothing ventured, nothing lost” so they just cut off from all values altogether. This was part of the ancient world’s – what they call “failure of nerve.” Through the end of the fourth century, through the end of Aristotle, they were talking about ways of achieving values, whether mystical or otherwise. After that they were talking about ways of escaping the penalty of values and then that went into escaping this life, and then that went into Christianity. So Stoicism was one of the collapses of the ancient world.

And then the next question asks about Epicurus. The same thing, except he was not religious, he was a materialist, but he was a funny materialist because he believed in free will. And they asked him, “How do you? – He was an atomist – How do you reconcile free will with all the atoms that merely react by hitting each other?” And he said that “Well some atoms swerve, they just swerve causelessly, and when they do that’s free choice.”

Obviously, she [Ayn Rand] didn’t believe in that, she didn’t believe in hedonism, which was his version of ethics, and he too was part of the “failure of nerve” because his version was not “go out and get as much pleasure as you can.” His version was to withdraw into the garden, and the line was “neither eat drink nor make merry lest tomorrow you die.” So in order to have pleasure you avoid anything that could upset you, so even though on the surface it was so different from Stoicism, it’s not.

I think it largely useless, and too far over the line of my intent to keep this blog focused on Epicurus, to attempt to unwind the many inaccuracies in these paragraphs. I am sure the Stoics would dispute some of the details of Peikoff’s characterization of their views, but I will leave that to them, and in fact there is a great deal of truth in Peikoff’s characterization of the essential error of Stoicism.

In regard to Epicurus, however, I will have to bite my tongue to keep from responding in kind to this disrespectful and woefully inaccurate summary of Epicureanism. Readers of this blog can cite the obvious problems, and anyone who cares to explore these topics in detail can find all of these slanders extensively refuted in Norman DeWitt’s Epicurus and His Philosophy. But to be clear:

- Unlike Objectivism today, Epicurus took seriously the need to establish a scientific basis for the nature of “the soul” and the existence of free will. Epicurus certainly never said that the swerve of the atom “was” free will, or “free choice,” but only that the free will which we see to exist in men must have a basis – not in a supernatural soul – but in an actual, real, physical, Natural characteristic. Epicurus set out to establish a rational and compelling system of thought capable of freeing the average man from the straightjacket of fear of the gods and fear of death. His achievement was revered throughout the ancient world, its renown has survived to this very day, and the superiority of Epicurus to every other ancient philosopher has been pointed out to the modern world by no less than Thomas Jefferson himself. Will anyone have heard of Objectivism in two thousand years?

- Peikoff’s claim that Epicureanism was not oriented toward maximizing pleasure is as wrong-headed as are his claims that Epicurus preached withdrawal into the garden, that he preached against eating, drinking, and making merry, and that he preached avoiding anything upsetting as the proper means of gaining pleasure. Certainly these slanders are not original to Peikoff, and they have been around at least since the time of Cicero, but none of these errors can survive a study of the full context of the Epicurean texts, such as that conducted by Norman DeWitt. No reader of this blog, no reader of the work of DeWitt, and no one who studies the Epicurean texts sufficiently will fail to appreciate that these are simply echos of the distorted and selective readings of opponents who sought to place Epicurus in the worst light possible. Withdrawal into a garden can indeed be appropriate, but only when circumstances make the outside world hostile. Neither Cassius nor Atticus nor Lucretius nor Plotina nor any number of other Epicureans saw any reason to hide their views when circumstances allowed the freedom to proclaim them, and Epicurus himself gave no hint that he considered himself a prisoner within walls against his own will. Numerous passages establish that the pleasures of eating drinking and making merry were not only recommended, but were set forth as examples of Nature’s instruction to man of the proper way to live. And Epicurus could not have been more clear that on occasion pain (even “anything upsetting” in Peikoff’s words) is to be sought out and embraced when it rationally leads to the experience of greater pleasure or the avoidance of greater pain.

To bring this post to a close, it was not Epicurus who experienced a “Failure of Nerve.” It was the Stoics and their cousins in Platonic philosophy and competing religions whose nerve was incapable of trusting the senses, whose eyes were blind to the merit of Epicureanism, and whose cowardice paved the way for the Dark Ages. What’s done is done, but today it is quite a shame to see so many who would gain so much from Epicurus deprived of that opportunity because of the failure of their intellectual leaders to pay attention to the true philosophy of Epicurus.