An Epicurean Message Hits Home 2000 Years Later In London

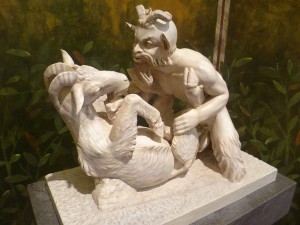

This past week, I was lucky to be able to attend a worldwide simulcast movie-theater presentation highlighting the new exhibit at the British Museum in London on artifacts from Pompeii and Herculaneum. The presentation was excellent, but one particular part of it struck home as worthy of mention here. One of the more noteworthy pieces on exhibit, which is apparently generating as much talk as any other, is the famous “goat sex” statue from the Villa of the Papyri, which is of course the home of our famous Epicurean library.

This past week, I was lucky to be able to attend a worldwide simulcast movie-theater presentation highlighting the new exhibit at the British Museum in London on artifacts from Pompeii and Herculaneum. The presentation was excellent, but one particular part of it struck home as worthy of mention here. One of the more noteworthy pieces on exhibit, which is apparently generating as much talk as any other, is the famous “goat sex” statue from the Villa of the Papyri, which is of course the home of our famous Epicurean library.

The point I want to focus on here was the reaction of the two stars of the presentation, Mary Beard and Bettany Hughes, to the goat statue. Mary Beard was the “expert” designated to explain the significance of the artifacts, and Bettany Hughes was the designated nice-looking narrator whose role was both to spark interesting dialogue and to appeal to the men in the audience who were bored by looking at the artifacts. Despite their roles, I want to suggest the possibility that the expert’s opinion of the statue was probably very wrong, and the untrained reaction of Bettany Hughes was probably exactly what the Epicureans of the day intended.

Mary Beard gave the standard academic view, with a big smile and twinkling eyes. My paraphrase: this statue was found in an Epicurean garden, don’t ya know, and the Epicureans were into pleasure, don’t ya know, and this is just another example of the erotic ways those wild and crazy Epicureans engaged in all sorts of fantasies (big smile).

Mind you this is not written to be critical of Mary Beard. No doubt hers is the standard view – but in my view it is quite likely that she was very wrong.

Bettany Hughes, on the other hand, gave the kind of response that intellectuals love to look down on as provincial. But in truth her reaction is likely just what the Epicureans intended. Hers was the kind of reaction that females in most ages before us gave, before we learned in very recent years how cool it is to explore new ways of portraying graphic sex. Bettany Hughes gave the response that has been the norm for 2000 years – she carried on about how shocking the image was, how disturbing it was, and how she could hardly bear to look at it without being more disturbed every second.

That, my friends, might well have been exactly the reaction that the Epicureans intended when they added the statue to their collection. Not because the Epicureans were grossly emotional about sex, because all indications are they were not. What they were moved to be emotional about, however, what they did love to ridicule and make fun of, and what they did find disgusting was the absurdity of the common religions and legends.

As we know from Lucretius, from Philodemus, and probably from other references which escape my mind at the moment, it was a constant theme of Epicureans that Pans and Centaurs and mythological creatures like that not only did not exist, but could not exist under the laws of Nature. I would suggest that the ancient Epicureans could not have failed to see what Bettany Hughes saw two thousand years later — that this image is, despite the beauty of its workmanship as a statue, is revolting and disgusting! What better way to ridicule and reinforce in the mind of current and potential Epicureans the true nature of the common religions? What better way to illustrate how unreal, how ridiculous, and how offensive to true notions of divinity the legends of the poets and the common folk had become, than to portray the seedy details of what the religions held to be true?

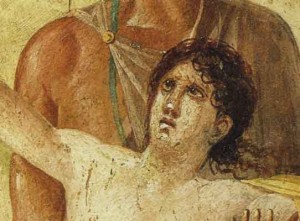

Consider that Lucretius, from much the same time period, employed the image of the murder of Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon, in much the same way. What better way to highlight the horror and pure evil that comes from religion than to portray its handiwork in stark detail – the murder of a totally innocent girl at the whim and direction of the priests! The portrayal of Iphigenia below (from Pompeii) might well have been intended to serve much the same function.

I would suggest that must the same effect would be obtained by portraying Abraham sacrificing Isaac, not in the romanticized way illustrated here, but in the stark reality of the horror of the scene.

How many other outrageous scenes from the Christian, Islamic, and Jewish religions could be portrayed in the visual arts and used in a similar way? Would not the bitter truth of having to look at the horrors that religion glosses over have an excellent effect in liberating the mind? Far too many examples come to mind to list here, but thanks to Bettany Hughes, I think we’ve been given a useful illustration of the good effects that such portrayals might generate.

So as we close, meditate on the goat-sex statue in all its glory, and remember what Lucretius wrote in De Rerum Natura: “So great is the power of religion to persuade men to evil!”