An Aristotelian Indictment Against Epicurus

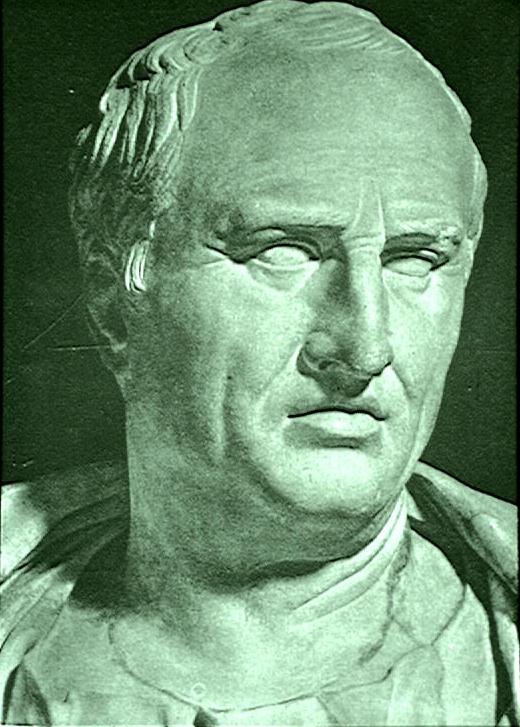

Since at least the time of Cicero, Epicurus and his philosophy have been vigorously attacked by Platonists, Stoics, Peripatetics, Skeptics, and all varieties in between. The attack continues to this day.

We are all familiar with the standard religious critique of Epicurus, but for today’s post I have found a source that constitutes a bill of indictment from an unusual perspective – modern-day Objectivism. While Epicureanism has many differences with a group that idolizes Aristotle and demotes Epicurus to a footnote in history, this list of charges is superior to many that we see. Despite their many differences, Objectivism shares Epicureanism’s non-religious outlook and emphasis on personal happiness, so this critique cannot be dismissed as the normal rantings of religionists.

The charges presented here stem from a source that is over forty years old, but which is still being distributed today. In my view these charges (along with the standard academic view from which they derive) have kept many thousands of people from learning the truth about about Epicureanism.

Over the next weeks and months I will work toward preparing a detailed response to each charge. I should note that the relentless deluge of misrepresentation which confuses Epicurean ideas with Stoicism has infected this list of charges. It is my hope that seeing this list in raw form, as part of an overall indictment from a non-religious source, will help us separate true Epicureanism from the accretions of Stoic apathy, negativism, and suppression of emotion that is no part of the true philosophy of Epicurus. For example, the concluding charge here is inflammatory – but I see it as indeed valid as the logical conclusion of Stoicism. The Stoics and Platonists from which they derive indeed saw unity with their own vision of godhood as its goal, but this is most certainly the opposite of true Epicureanism.

I hope fans of Epicurus will think about how you would yourself respond to these charges. I welcome suggestions as we work through the responses.

For now, the indictment:

- Aristotle was the high point of Greek Philosophy because he held that man lives in a world that is fully real and scientifically intelligible. Aristotle was great because he held that man has a mind competent to gain objective knowledge of reality by the use of reason and logic based on the evidence of the senses. Aristotle held the good life to be eudaimonia (happiness) and the crown of the virtues to be pride.

- All philosophers for two hundred years after Aristotle were second-rate minds and derivative of what came before.

- The main concern of all Greek philosophers after Aristotle (including Epicurus) was how to live in a world of fear, anxiety, and insecurity, and they contain within them a streak of malevolence that focused on how to escape from being hurt in a hostile universe.

- The goal of Epicurus was to achieve happiness, and he believed the two main obstacles standing in the way of that goal were fear of the gods and fear of death. From this starting point, and not by looking independently at reality, he decided to adopt the physics he thought most convenient to his purpose – the atomism of Democritus. This brands Epicurus as a philosopher of the second rank, at best.

- The gods of Epicurus live in seclusion and have no ability or desire to influence human life. This brands Epicurus as essentially an atheist.

- In order to preserve free will, Epicurus developed the doctrine of the swerve, but in doing so he created a hopeless theory that destroys the law of cause and effect.

- The swerve of Epicurus is ENTIRELY causeless. It is not simply that we do not KNOW the cause, but there IS no cause for the swerve. This is sheer chance, and this hopeless theory creates an indeterministic universe where NOTHING is certain. It does not even salvage free will, because any will that we have is subject to that same chance and is therefore not within our power to control.

- Epicurus’ theory of knowledge is without value, originality, or influence.

- Epicurus’ ethics constitute mere “hedonism,” which is incorrect because life is the standard of value, not pleasure or even eudaimonia.

- Epicurus’ distinctive contribution to hedonistic ethics was his means for achieving it, which arose from his malevolence and insecurity. His means boil down to this: the more you care about anything the more it can hurt you, so the way to live is to be indifferent to everything. Our goal is therefore to be independent not just of other men, but independent of reality itself.

- Epicurus held that it is hopeless to attempt to change or improve the world, so your goal must be to stop it from affecting you in any way. The wise man will therefore conquer his emotions; he will stop feeling; he will become essentially emotionless, and this is the great virtue of Epicurus, to become emotionless.

- No Epicurean would seek a life of achievement, creation, action, engagement with the world, or fighting for his values. The motto of an Epicurean would be “Nothing ventured, nothing lost,” or “Better safe than sorry,” or “Wall yourself off from reality and then it can’t hurt you.” The true Epicurean lives inside his walls with a few close friends and lets the world outside the garden go to hell.

- The greatest happiness for an Epicurean is the absence of strong emotion and the cessation of action. Happiness is something negative for an Epicurean – it is the state of not being hurt. The model of happiness for an Epicurean is a state of dreamless sleep. The goal is to be emotionless, which will make you independent of reality and numb to any pain or worry, and this is the meaning of happiness.

- Epicurus advocated a simple life with a few close friends about whom you do not care too deeply, because if one dies you simply shrug it off. Sex is harmful, but it is ok to engage in sexual intercourse so long as it is devoid of passion.

- Epicurus’s philosophy amounts to a turning away from life on earth. Epicurus advises us to withdraw, give up, retire from life, and don’t let ourselves be hurt. But Epicurus is not fully consistent, and he does not follow his advice to its logical conclusion – which is that death is his true ideal.