A Season Of The Year To Remember Fallen Epicureans

[As we appear to be on the verge of escalating another ill-considered war, this time in Syria, the following post, which is a repeat of a topic I have repeated this time of year for the last several years, seems particularly appropriate.]

[As we appear to be on the verge of escalating another ill-considered war, this time in Syria, the following post, which is a repeat of a topic I have repeated this time of year for the last several years, seems particularly appropriate.]

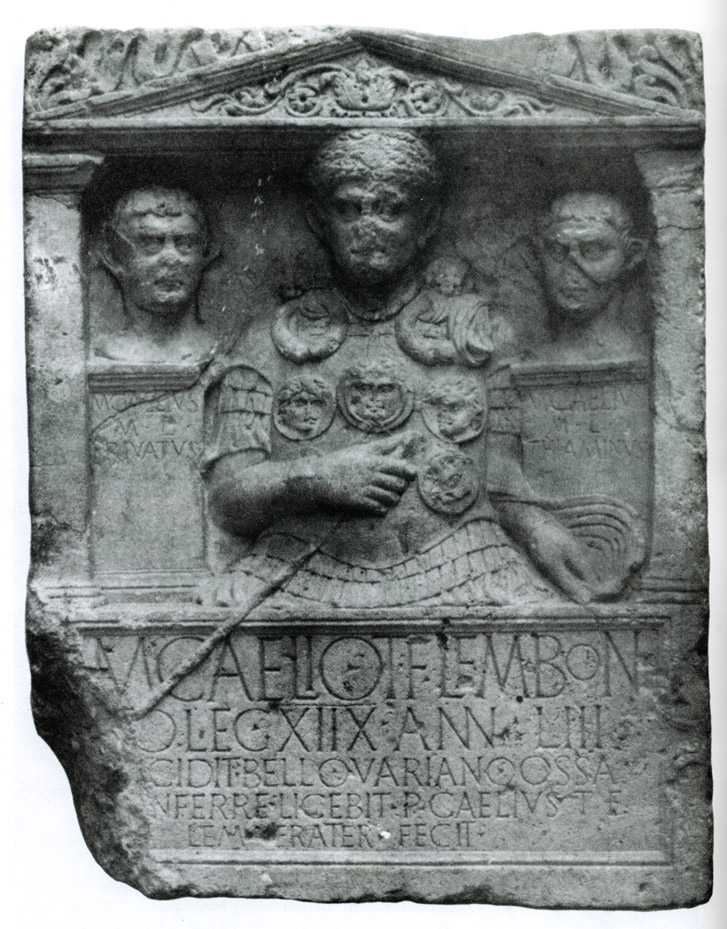

Translation of the inscription of the stone: “To Marcus Caelius, son of Titus, of the Lemonian voting tribe, from Bologna, a centurion in the First Order of legio XVIII, aged 53; He fell in the Varian War. His bones – if found – may be placed in this monument. Publius Caelius, son of Titus, of the Lemonian voting tribe, his brother, set this up.“

One of the things that motivates me in the study of Epicureanism is the knowledge that two thousand years ago a very large living breathing group of people walked the earth applying Epicurean ideas in their daily lives, and not just debating philosophy for the sake of academic argument.

The Fall of the year — late August, September, and early October — is a particularly good time to remember these living breathing Epicureans, and the vital force that Epicureanism exerted in the ancient world. That is because this was a time of year that a significant number of ancient Epicureans met untimely ends in three separate events to which we can relate because so much is known about them.

The first of the three that occurred this time of year was the Battle of Philippi, fought during the month of October in 42 BC. In that battle, one of the most famous Epicureans of the Roman world, Gaius Cassius Longinus, lost both his life and the hope of the Senatorial forces to preserve the Roman Republic. We are of course well familiar with Cassius’s Epicureanism from his letters to Cicero, and also from the discussion between Cassius and Brutus about the ghost of Caesar which was preserved by Plutarch. How the world might have been different if the Battle of Philippi had ended differently, the Republic had been reformed, and Rome had been led for any length of time by a devoted Epicurean!

The second of these three events occurred in early September of the year 9 AD, when the Roman world was shaken by the loss of three legions under Publius Quinctlius Varus at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in Germany. I am not aware of any Epicureans by name who were lost in that action, but it occurred only some fifty years after the death of Cassius, and Epicureanism was certainly a vital force in the minds of many educated Romans at the time. We know specifically from Cassius’s letters to Cicero that a number of military leaders of his own day Epicureans, and 9 AD was long before the rise of Christianity, so it is logical to presume that a number who were killed in that battle were Epicureans. I need to add to my list of things to research whether anything is known about the specific individuals who were lost at Teutoburg Forest.

Last of these three Fall events is one of the most famous disasters of the ancient world, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in late August of 79 AD. Here there is no need for speculation as to the participation of Epicureans. The eruption preserved for us the Epicurean library of Philodemus at Herculaneum, and the busts of Epicurus, Hermarchus, and Metrodorus found nearby. Not far away in Pompeii, the eruption preserved for us the famous “monkey skull” mosaic at the house of Marcus Vesonius Primus, which I believe to be firmly Epicurean in design.

Death comes for us all, but no group of people is as well prepared for it as Epicureans. Thus, as Epicurus taught, reflection on these events should not evoke sadness, but the opposite. The true realization we should take from this reflection is that there was once a time when large numbers of people lived their lives, and met their deaths, having followed Epicurus, embraced life, and found the happiness that so many never find.

We should work to rediscover, and apply to our own lives, the resolution that Epicurus urged on us, so that we too can one day say:

I have anticipated thee, Fortune, and entrenched myself against all thy secret attacks. And I will not give myself up as captive to thee or to any other circumstance; but when it is time for me to go, spitting contempt on life and on those who vainly cling to it, I will leave life crying aloud a glorious triumph-song that I have lived well.